Agarito, Algerita

Berberis trifoliolata Moric.

Synonym - Mahonia trifoliolata (Moric.) Fedde

Berberidaceae (Barberry Family)

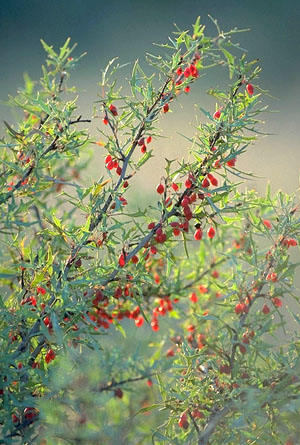

Agarito (algerita) is a small-to-medium, evergreen shrub that produces an abundant spring crop of red berries. Its leaves are spine tipped, appearing somewhat like holly, and spread out palmately in threes. Valued by both humans and wildlife, the red berries can be made into an excellent jelly that Texans have been producing for generations. Not only does agarito fruit make a great jelly, it makes great pies, cobblers, and a very refreshing drink when mixed with sugar (Tull 1987:213). Surprisingly, the documented medicinal uses of the plant far outnumber notations of its food use. Read on to explore the many uses of this interesting little shrub.

There are no ethnographic records for our species, Berberis trifoliolata, because its distribution does not overlap with the locations of any ethnobotanical studies. However, the berries, leaves, and wood or bark of Berberis trifoliolata are similar to the other species of Berberis growing in adjacent regions, including Berberis haematocarpa in the Trans-Pecos and Berberis repens in the Guadalupe Mountains. Numerous ethnographic accounts document the use of these and other Berberis species by the Native Americans of the Plains, the northern Southwest, and the Pacific Northwest. Virtually every part of the plant had a use for food, medicine, and dye.

Archeological Occurrences. Agarito has not been identified from archeological sites in the South Texas Plains, probably due to a lack of research. However, just west of the region, agarito berries and seeds were identified in the well-preserved rockshelter deposits of the Lower Pecos (Dering 1979). Wood from agarito was noted in samples collected from an Indian campsite in Edwards County, just northwest of Uvalde (Quigg 2005). More excavations and analysis will likely uncover additional archeological evidence of this useful plant.

Food Use. Despite the fact that agarito is a legendary specialty food in Texas few Native American groups consumed the berry. Hodgson (2001) did not report any ethnographic documentation of its use as food by native peoples in the Sonoran Desert, stating that alkaloids were present not only in the roots, but also in the berries. This is probably why the tart flavor and beautiful color of the berries works well in a jelly, a foodstuff which is made with sugar and consumed in small quantities. The Chiricahua and Mescalero Apache ate the fruit fresh or made jellies with it. The process of making jelly involved mixing in an unidentified sweet substance (Basehart 1960; Castetter and Opler 1936:46). I suspect that the substance is probably sugar, and making jelly is a post-contact practice. Other groups that are reported to consume fresh berries include the Yavapai, Jemez, Blackfoot, and Cheyenne (Castetter 1935).

Medicinal Uses. Alkaloids in the roots provide the medicinal qualities of Berberis, and numerous groups used decoctions, poultices, and infusions to treat ailments ranging from fevers to stomach troubles and open wounds. The Havasupai used Berberis repens roots in a decoction as a laxative and a treatment for an upset stomach (Weber and Seaman 1983). The Ramah Navajo and some groups in the Pacific Northwest also used the roots as a laxative (Vestal 1951; Turner et al. 1983). Indians in Mendocino County, California used a decoction of the root bark to treat stomach ailments (Chesnut 1902).

Antiseptic qualities of the root and root bark are suggested by its use to treat wounds, skin or gum problems. Mescalero Apache soaked shavings of the inner wood in water and used it as an eyewash (Basehart 1960:49). The Ramah Navajo used a cold infusion to treat scorpion bites. The Hopi chewed the plant bark to treat gum diseases. Penetrating qualities of the plant are exhibited by its use to treat aches or pains. The Navajo used a decoction of the leaves and twigs to treat stiffness in joints (Elmore 1943). Urinary or reproductive tract treatments include use of the decoction to treat venereal disease by the Paiute (Kelly 1965). In Washington, Reagan (1936) observed the native inhabitants of the Olympic peninsula using a tea made from the roots as a "blood remedy" for an undefined ailment.

Other Uses - Dye: Many groups used Berberis as a dye. The Havasupai and Navajo dyed buckskin with the plant. Basketry was dyed yellow by the Walapai (Weber and Seaman 1985). The Mescalero dyed hides yellow with a mixture of root shavings from Berberis (Basehart 1960:49).

Ceremonial. The Ramah Navajo used the whole plant as an internal cleansing agent (Vestal 1951). Regan makes a cryptic reference to its use in ceremonies by the White Mountain Apache "because of its yellow wood" (Reagan 1929:155). The Hopi used the root and leaves for ceremonies. The Hopi used the yellow root and the leaves in the Home Dance. The Zuņi crushed the berries and used them as face paint and paint for ceremonial objects. Berberis use by the Zuņi was the exclusive right of the individuals in charge of the ki-wit-siwe, which were the chambers dedicated to anthropic worship. The plant was said to belong to them (Stevenson 1904:62; 1915:88).

References

Basehart, H.

1960 Mescalero Apache Subsistence Patterns and Socio-Political Organization. The University of New Mexico Mescalero-Chiricahua Land Claims Project Contract Research #290-154. University of New Mexico. Albuquerque (perfect-bound copy).

Castetter, E.

1935 Uncultivated Native Plants Used as Sources of Food. Ethnobiological Studies in the American Southwest. Vol. I. The University of New Mexico Bulletin, Biological Series 4(1). Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Castetter E. F., and Morris Opler

1936 The Ethnobiology of the Chiricahua and Mescalero Apache. A. The Use of Plants for Foods, Beverages, and Narcotics. Ethnobiological Studies in the American Southwest. Vol. III. The University of New Mexico Bulletin, Biological Series 4(5). Albuquerque.

Chesnut, V. K.

1902 Plants Used by the Indians of Mendocino County, California. Contributions from the U.S. National Herbarium 7(3):291-422.

Colton, Harold S.

1974 Hopi History and Ethnobotany. In Hopi Indians edited by D. A. Horr. Garland, New York.

Dering, J. Phil

1979 Pollen and Plant Macrofossil Vegetation Record Recovered from Hinds Cave, Val Verde County, Texas. Unpublished Masters Thesis. Texas A&M University. College Station, Texas.

Elmore, F. H.

1944 Ethnobotany of the Navajo. University of New Mexico Bulletin, Monograph Series 1(7). University of New Mexico Press. Albuquerque.

Kelly, Isabel T.

1965 Ethnography of the Surprise Valley Paiute. Kraus Reprint Corporation. New York. [Reprint of 1934 edition. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 31:67-210].

Quigg, J. Michael, J. D. Owens, G.D. Smith, and M. Cody

2005 The Varga Site: A Multicomponent, Stratified Campsite in the Canyonlands of Edwards County, Texas [Draft]. Technical Report No. 35319. TRC, Inc. Austin, Texas.

Reagan, Albert B.

1936 Plants Used by the Hoh and Quileute Indians. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 37:55-70.

Stevenson, Matilda Coxe

1904 The Zuni Indians: Their Mythology, Esoteric Fraternities, and Cermonies. Twenty-third Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology [1901-1902] Washington, D.C.

1915 Ethnobotany of the Zuni Indians. In Thirtieth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. [1908-1909], pp. 35-103. Washington, D.C.

Tull, Delena

1987 Edible and Useful Plants of Texas and the Southwest: A Practical Guide. University of Texas Press. Austin.

Turner, Nancy J., John Thomas, Barry F. Carlson, and Robert T. Ogilvie

1983 Ethnobotany of the Nitinaht Indians of Vancouver Island. British Columbia Provincial Museum. Victoria.

Vestal, Paul

1952 Ethnobotany of the Ramah Navaho. Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology 40 (4). Harvard University. Boston.

Weber, Steven A., P. David Seaman

1985 Havasupai Habitat: A.F. Whiting's Ethnography of a Traditional Indian Culture. University of Arizona Press. Tucson.