Rancho de las Cabras

Local ranchers had long been aware of the crumbling stone walls that protruded from a tangle of thorny brush at this Wilson County site. Situated on a high point above the San Antonio River, the ruin was a distinctive landmark. And given its proximity to San Antonio, with its rich Spanish Colonial heritage, some thought it might even be another Spanish mission.

After researchers sifted through historic maps and records, however, it became apparent that the site had to be the ranch of Mission San Francisco de la Espada—Rancho de las Cabras, or the Ranch of the Goats. The ranch was built in the 1750s after early San Antonio residents—Canary Islanders—complained that mission cattle were trampling their crops. Espada had large herds—as many as 1,150 head of cattle, 740 sheep, 90 goats, 30 horses and oxen, according to a 1745 report. To meet the resident’s demands, the friars arranged for the animals to be moved to mission grazing lands some 30 miles to the southeast, and appointed Indians from the mission to tend to their needs. Apparently, the herders and their families were left largely on their own, as long as the animals were well cared for and the designated allotment of animals was supplied weekly to meet the mission’s needs. Removed from the protection of the soldiers at Presidio San Antonio de Bejar, the native workers were vulnerable to attacks by Lipan Apaches and other hostile raiders.

Researchers found little in historic records describing the structures at the ranch complex. The 1772 inventory of Mission Espada made on the eve of its closing, however, described the compound as consisting of four jacals, or structures of upright poles with thatched roofs, one of which was sometimes used as a church or shrine; corrals and pens; and a fenced field for corn. A later account mentions that 26 persons lived at the ranch. This likely included herders and their families.

Ethnohistorian T. N. Campbell, attempting to ascertain which native groups might have been represented at the ranch, found a list of 11 names in Mission Espada records for the period 1753-1767. These included the Assaca, Caclote, Caguamama, Carrizo, Cayan, Gegueriguan, Huarique, Saguiem, Siguipan, Tuqrique, and Uncrauya. Although we likely will never determine which group or groups were represented at the rancho, Campbell believes none of the 11 were native to the area, nor did they speak the Coahuiltecan language. Rather, all of the groups were from extreme south Texas and the Mexican state of Tamaulipas and may have been remnants displaced by Spanish colonies established by Jose de Escandon along the Rio Grande river around 1750.

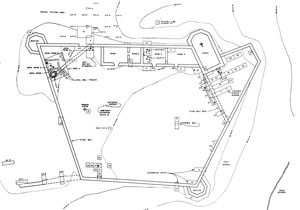

When archeologists visited the site in the 1970s, they found a large standing ruin, enclosed within a perimeter wall of sandstone blocks, remains of several rooms, and bases of defensive towers, or bastions. In 1976, the site and adjacent acreage was acquired by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Archeologists from the Center for Archaeological Research at the University of Texas at San Antonio were contracted to conduct field investigations prior to the historical development of the site for the public. In month-long stints over a period of five years, archeologists from UTSA-CAR mapped the site, tested along interior walls, and probed trash heaps near the two entry ways where gates once were located.

They determined almost immediately, based on differences in stone at different points, that the present outline of the compound is not the original, and that there had been at least two different building phases. Later additions after 1772 apparently included extensions to the wall and completion of a chapel. The hexagon shaped compound was accessed by two gates. Archeologists also found a kiln for making plaster, likely from the chapel interior. Postholes around the south wall were determined to represent jacals, and household items were found on floors.

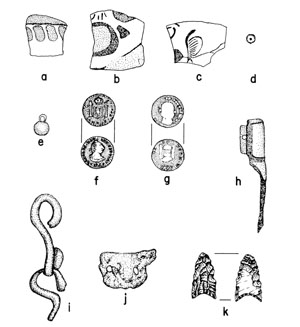

Most artifacts were found in large trash heaps, or middens, located outside the wall. In addition to chipped-stone tools and crude, bone-tempered pottery, which pointed to the persistence of earlier native traditions, archeologists found the remains of imported ceramics, including tin-enameled, Mexican majolicas, oriental porcelain, and French faience; coins; gunparts, and other metal objects; and an array of ornate personal items—fancy metal buckles, jewelry, and crucifixes. They also found chipped-stone gunflints, indicating use of European flintlock guns, and a quantity of bone, indicating a diverse diet of domestic animals augmented by wild resources including turkey, deer, javelina, opossum, squirrel, fish, and turtle.

One of the research interests of the archeologists had been to try to ascertain the degree to which acculturation had taken place among the Indian neophytes, particularly when separated from the mission fold. They found a surprising indication of adherence to mission teachings, given that a chapel was erected, religious items such as rosaries were employed, and European merchandise was used. Although traditional native practices continued, the native vaqueros apparently fulfilled their duties in tending the herds.

As noted by UTSA-CAR archeologist Anne Fox, in a 1989 article on Rancho de las Cabras:

Life at the ranch, away from direct supervision and under extreme stress of threat of Indian attack, might tempt Indians who were a bit shaky in their indoctrination as Spanish citizens to slip back to their earlier habits. The fact that they apparently did not could be an indication that only Indians of long standing and proven loyalty to the mission were chosen for this job since it was so essential to the well-being of the mission residents.

The site has been acquired by the National Park Service and there are plans to include it within the San Antonio Missions National Historic Park Trail.

Print Sources

Campbell, T. N.

1985 Appendix A. Rancho de las Cabras and the "Cabras" Indians of Southern Texas: Correction of Historical Errors. In Archaeological Survey and Testing at Rancho de las Cabras, 41WN30, Wilson County, Texas, Fifth Season. Archaeological Survey Report 144. Center for Archaeological Research, University of Texas at San Antonio.

Fox, Anne A.

1989 The Indians at Rancho de las Cabras. In Columbian Consequences: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives on the Spanish Borderlands West, edited by David Hurst Thomas, pp. 259-268. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington.

Ivey, James E. and Anne Fox

1981 Archaeological Survey and Testing at Rancho de las Cabras, 41WN30, Wilson County, Texas. Archaeological Survey Report 104. Center for Archaeological Research , University of Texas at San Antonio.

Sanez de Gumiel, Juan Joseph

1772 Relación del Estado en que se hablan todas y cada una de las misiones, en el ano de 1762. In Documentos Para la Historia Eclesiastica y Civil de la Provincia de Texas o Nueva Philipinas, 1720-1779, edited by Jose Purrua Turanzas, pp. 245-275. Colleción Chimalistic de Libros y Documentos Acerca de la Nueva Espana, vol. 12, Madrid.

Taylor, Anna J. and Anne A. Fox

1985 Archaeological Survey and Testing at Rancho de las Cabras, 41WN30, Wilson County, Texas, Fifth Season. Archaeological Survey Report 144. Center for Archaeological Research , University of Texas at San Antonio.

See also the NPS website for Rancho de las Cabras:

http://www.nps.gov/archive/saan/

visit/RanchodelasCabras.htm

|

|

|

|

|