Wild Onion [Allium spp.]

The small bulbs of the genus Allium, known commonly as wild onion or wild garlic, grow throughout the Plateaus and Canyonlands region and may have been an important seasonal food source for native peoples, perhaps even a staple. Wild onions grow most densely on relatively well-watered terraces along streams and rivers, but can be found widely. There is growing archeological evidence that wild onions were harvested in bulk and baked in earth ovens.

Details

The most widespread of the Allium species, Allium drummondii and Allium canadense, grow throughout the region and throughout much of North America. All members of the genus Allium are edible, but some of the species may have occurred in densities high enough that the plant could be eaten as a staple, at least on a seasonal basis. It is not possible to identify an archeological specimen to the species level because many of the distinctions are made with combination of elements of the flower, fruit, and other characters that don't survive even in the dry rockshelter environments of southwest Texas.

Archeological Occurrence

In Hinds Cave, the only rockshelter site for which we have quantitative data, onion remains were the third most commonly occurring edible plant part in an Early Archaic context, and the fifth most commonly occurring in the Late Archaic context (Dering 1999:663). These data suggest that bulbs were consumed in large quantities, not as a condiment but as a staple. The coprolite data also confirm the importance of wild onion, where it was noted in 40-55% of the coprolites in two studies (Williams-Dean 1978; Stock 1983).

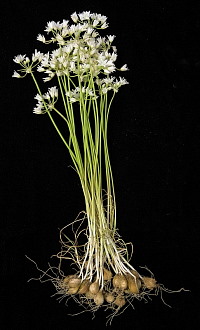

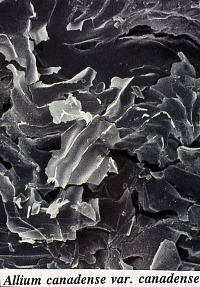

All of the Allium bulbs recovered from the Hinds Cave deposits consisted of dry, brown or tan fibers that look like tiny nets wrapped around the bulb. In the Hinds Cave specimens, some of the space between some fibers is filled with a thin membrane. This is characteristic of a few onion species, including Allium drummondii. Along the southwestern edge of the Edwards Plateau, Allium drummondii is the most common of the onion species, growing in relatively high densities (see photo). Although we can not be absolutely certain, the Drummond onion was probably the primary Allium species consumed by the prehistoric inhabitants of the region.

Native Accounts: Allium is often mentioned as an addition to other dishes, primarily meat, or simply mention that it was used for food. Regarding Allium drummondii, the Lakota used the bulb for "food" (Rogers 1980), the Cheyenne and Pawnee, as an addition to meat dishes (Gilmore 1977; Grinnel 1972). The Ramah Navajo boiled meat along with onion bulbs (Vestal 1952). In California, there are references to more intensive use of onion. Other species were similarly used; the Western Apache boiled blood in a deer stomach with onions for flavoring (Buskirk 1986).

In his 1952 article, Barrett notes that the Pomo of northern California baked onions in an underground oven. The Surprise Valley Paiute collected Allium in large quantities, two to five sacks at a time. They dug a pit and built a fire of unspecified size to which they added small stones. The food load was placed in the oven, covered with grass and earth, and left overnight (Kelly 1933:102).

The economy of both the Paiute and the Pomo focused much more on gathering plants than either hunting or farming. This may be why they were still utilizing wild onions more as a main dish, rather than a condiment. On the Edwards Plateau, it is likely that the Native Americans were using wild onions both as a primary, but seasonal, source of carbhohydrates and as a supplement.

Nutrition

Published analyses of fresh Drummond onion bulbs found that they contain 70% water, 1.7% reducing sugar, and 18.1% non-reducing sugar (Yanovsky and Kingsbury 1938). The non-reducing sugar represents long-chain carbohydrates, primarily inulin, which humans cannot digest. Inulin has to be exposed to heat for long time periods to be converted to digestible sugars, and baking in an underground pit is the most widespread technique that Native Americans utilized for this purpose.

References

Barrett, S. A.

1952 Material Aspects of Pomo Culture: Part One Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee 20:1-260.

Buskirk, Winfred

1986 The Western Apache: Living with the Land Before 1950. University of Oklahoma Press. Norman.

Gilmore, M.R.

1977 Uses of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region. University of Nebraska Press. Lincoln.

Grinnell, G. B.

1972 The Cheyenne Indians, Vol. 2, Their History and Ways of Life. Lincoln. University of Nebraska Press.

Kelly, Isabel

1933 Ethnography of the Surprise Valley Paiute. University of California Publications In American Archaeology and Ethnography 31:67-210.

Rogers, D. J

1980 Lakota Names and Traditional Uses of Native Plants by Sicangu (Brule) People in the Rosebud Area, South Dakota. St. Francis, SD. Rosebud Educational Society.

Vestal, P. A.

1952 The Ethnobotany of the Ramah Navaho. Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology 40(4):1-94.

Yanovsky E. and R. Kingsbury

1938 Analyses of Some Indian Food Plants. Association of Official Agricultural Chemists 21(4):648-665.

Hide Details

![]()