Stratigraphy

The deposits in Hinds Cave formed over at least 11,000 years, beginning at least as early as Late Paleoindian times before 9,250 B.C. and continuing into modern times. The deposits consisted of a few predominately natural layers and many layers composed mostly of cultural materials – things that people brought into the cave in prehistoric times. The natural layers were mainly limestone cave dust with some limestone roof spalls and an admixture of small, broken animal bones probably left by predators (in owl pellets, for instance). But most layers were made up mainly of cultural debris including thick layers of plant fiber and fragmented burned rocks (spent cooking stones), and thinner layers of ash, prickly pear pads, and human waste (feces and urine-compacted soil). In general, the lower deposits had more cave dust and less fiber, while the upper deposits had thick and extremely well preserved fiber. The uppermost deposits were disturbed by livestock, mainly goats, and augmented by their dung.

In the 1930s, if not earlier, people began to dig into the deposits in search of perishable artifacts. There is no telling how many different collectors dug into the site – many of them sneaked onto the property from the nearby Pecos River without the landowner’s knowledge. It was, in fact, a collector who first alerted archeologists to the existence of Hinds Cave. By the mid-1970s when the archeological investigations took place, most of the uppermost deposits in the rear and relatively flat areas of the shelter had been churned up by digging and many items probably including at least one infant bundle burial had been removed by collectors. The archeologists from Texas A&M excavated no more than 5% of the site – some 50 cubic meters. They removed and saved all of the artifacts and much of the plant and animal remains they encountered. The current condition of the shelter is not known, but there were reports of continued uncontrolled digging in the 1980s and 1990s. We suspect that none of the upper deposits remain intact today.

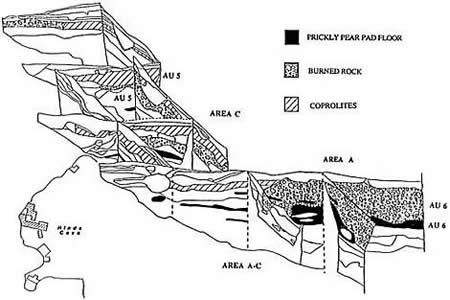

The stratigraphy (layering) of the Hinds Cave deposits was very complex and consisted of easily visible layers the excavators called “lenses” (macro-layers), some of which were made up of many thin micro-layers or lamina. The lenses ranged in thickness from less than 5 centimeters (2 inches) to more than a meter (over 3 feet). The micro-layers were sometimes paper-thin—just a few millimeters (less than 1/8 th of an inch) and often impossible to peel apart. The layering was not, however, arranged in a textbook layer-cake fashion. Instead many of the layers were convoluted and reflected the fact that Hinds Cave was dug into many times by prehistoric peoples and, in some areas of the cave, by critters such as burrowing animals. When Hinds Cave was being used, its the surface would have been quite uneven and marred by pits, piles, and winding paths. Through time, these topographic features weathered and filled in with loose sediments.

The people who lived in the cave dug various pits that the archeologists could recognize and, doubtlessly, many more that could not be traced. Some of the visible pits were used for cooking or food processing and others were used for sleeping, such as the shallow pits filled with layers of grass. The archeologists called the discrete pits and other special layers features and paid special attention to these because they realized that most represented a single occupational event or series of closely spaced events that happened during one particular use episode.

Recognizing, following, and keeping track of all these lenses and features and their contents was a major challenge made all the more difficult because Hinds Cave was excavated during two major seasons, a year apart. The field crew was made up of a mix of trained archeologists and their assistants, volunteers, graduate students, and undergraduates, most of whom were learning on the job. Personnel changed from year to year, although two key graduate students—Glenna Williams-Dean and Phil Dering, and staff archeologist Ed Baxter—served as supervisors throughout both seasons of work.

The excavation and recording methods also changed during the course of the project as the archeologists learned more about the site and devised more sophisticated ways of separating the layers. For instance, the first year several small units were dug in arbitrary levels 10 or 20 centimeters thick. Soon the complexity of the layering was apparent and the first test pits and cleaned out holes left by looters to guide later excavations by “natural layers.” This term means that the excavators followed "naturally" existing layers, rather than arbitrary levels. Sometimes the natural layers were quite thick and lacked visible internal subdivisions, so arbitrary subdivisions within those thick layers were used to determine whether different kinds of materials were present within the thicker layers.

After returning from the site for the last time after a final brief work session in 1978, the archeologists realized that they needed to simplify the stratigraphy for analysis and meaningful comparison between excavation areas. During the earlier salvage excavations at nearby Amistad Reservoir (see Before Amistad), the archeologists typically lumped the smaller layers into major zones representing thicker deposits that could be fairly easily traced. Lead investigator Harry Shafer collapsed the Hinds Cave lenses into eight analysis units, which are equivalent to the zones used by the Amistad archeologists. These are described in the Analysis Units section.

Detailed profiles and profile descriptions were carefully done by the field archeologists. Unfortunately, no detailed and fully labeled final versions of any these have been published. Redrawn and simplified profile drawings have been published by several Hinds researchers and these can be accessed within this online exhibit.