The Mossy Grove Tradition

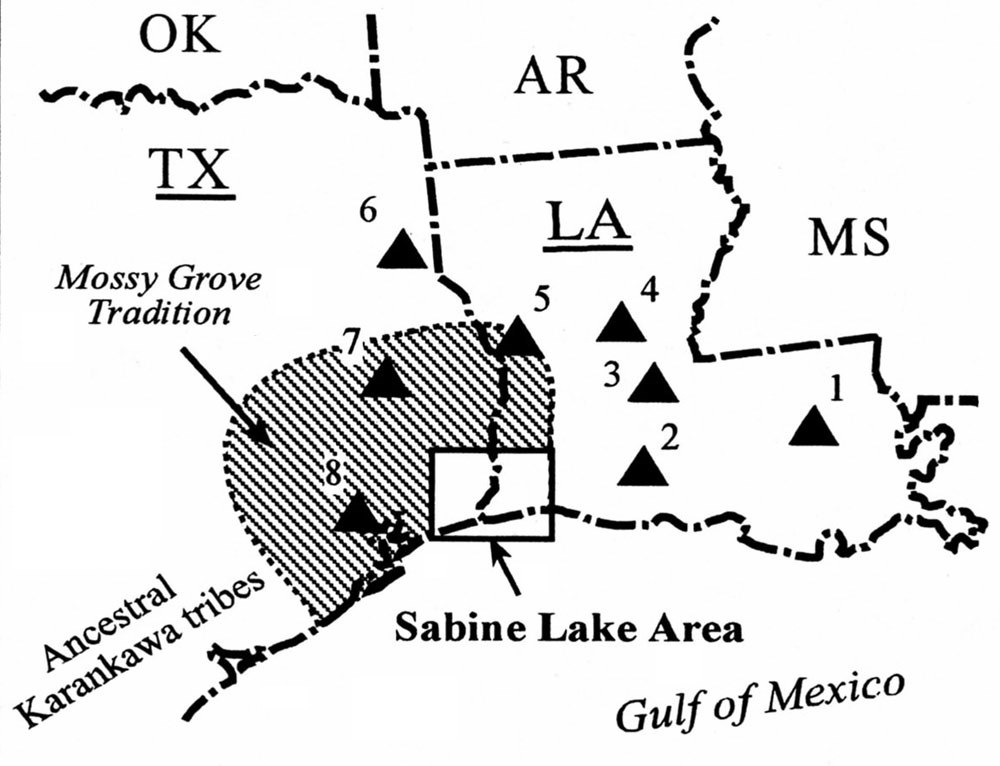

From roughly the late seventeenth to middle nineteenth centuries, the Sabine Lake vicinity—straddling the historical boundary separating French Louisiana and Spanish Texas—was known as the westerly limit of the Western Atakapa tribal territory. The Atakapa, along with their neighbors the coastal Akokisa and interior Bidai tribes, were among the populations whose cultures formed the southwestern periphery of the Southeastern United States culture area. In earlier times the western limit of this cultural traditions extended well into southeast Texas along the coast and inland.

While maintaining their separate ethnic identities, these three groups, and undoubtedly some as yet unidentified others, shared for an extended time period many cultural, technological, and linguistic similarities that were more or less distinct from the surrounding ethnic groups. By “extended time period” it seems fairly certain this means at least the past 2000 years and very likely longer, as we shall see. As a result, it can be useful at times to treat them together in combination and for this purpose Professor Dee Ann Story—a well-known Texas archeologist—suggested the name “Mossy Grove Tradition.”

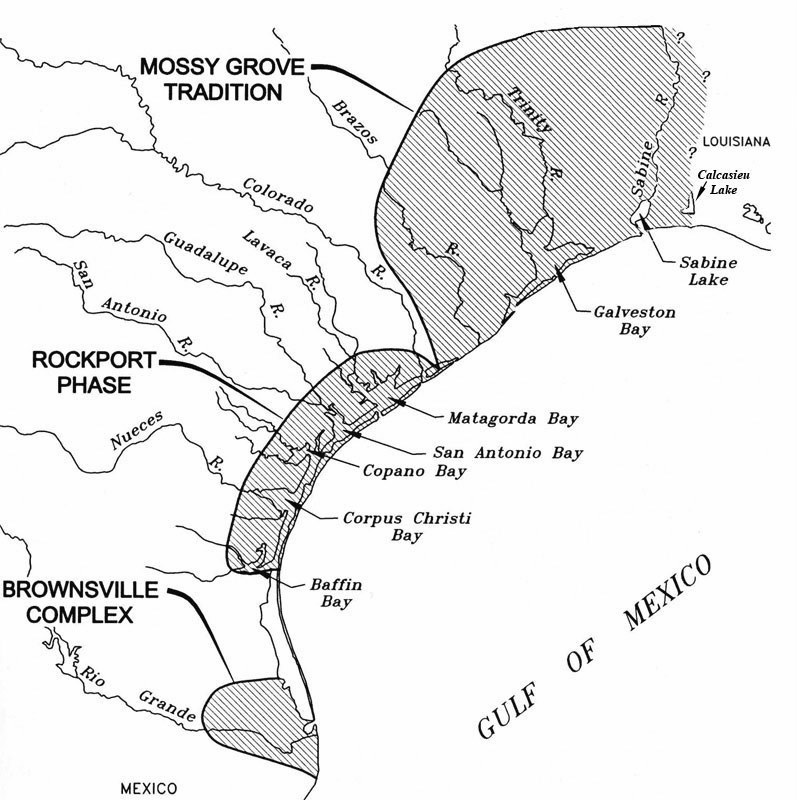

Some Mossy Grove tribes occupied coastal marshes and the coastal plain, while others frequented the adjacent interior woodlands of southeast Texas and southwest Louisiana. The eastward extent of the Mossy Grove Tradition is not yet known but a good guess is that it probably coincided with the territorial boundary between the Eastern and Western Atakapa, or roughly the east side of the Calcasieu River and Lake. To the southwest and west of Galveston Bay—probably as far as the Brazos River—they were bounded by nomadic tribes of the coastal prairies such as the Karankawa and their ancestors. To the north and east were sedentary or semi-sedentary agriculturalists or “moundbuilders,” including the Caddo-speaking peoples and various “lesser” groups who were allied with the Caddo.

Before European explorers and colonists entered the Gulf of Mexico, Mossy Grove peoples standing on the Gulf shore looking out to sea probably never saw maritime peoples whereas they surely knew that if they walked in any other direction far enough they would encounter other people. To the Mossy Grove peoples the Gulf was an impassable barrier—perhaps even thought to be the edge of the earth. Yet, if we can believe late 19th century Galveston physician and amateur historian J. O. Dyer, the Atakapa origin myth had their first people cast up from the sea in oyster shells.

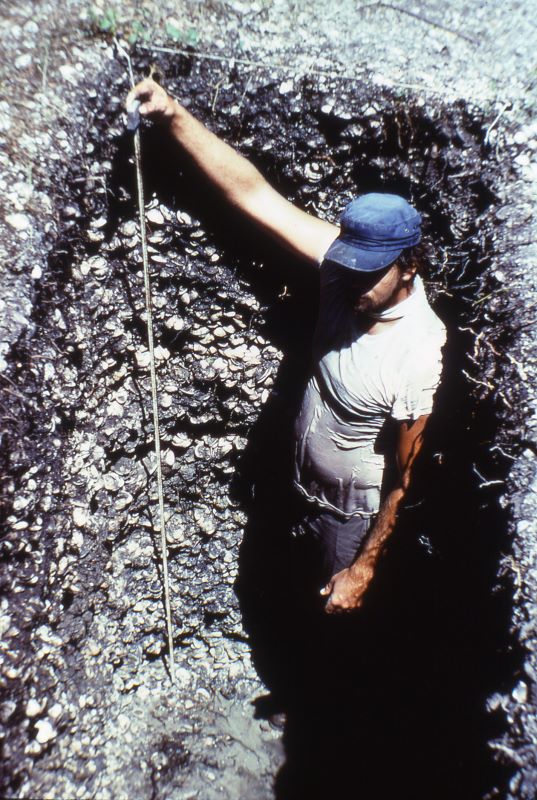

Despite some Mossy Grove groups living part-time on the seashore, coastal lagoons, estuaries, and marshlands, they were only slightly adapted to these resources and environments. Indeed, they were little more than scavengers along the seashore, while somewhat more skilled at exploiting the coastal lagoons and estuaries, and relatively more so in the coastal marshes. There they obviously gathered wild plant products, about which we have very little information, prodigious quantities of shellfish–mostly the brackish water clam Rangia cuneata–did some fin fishing, and relatively more hunting of small to large animals. While there must have been very large quantities of fish in the sea and estuaries, relatively few of their bones are found in early Mossy Grove archeological sites until relatively recently when weirs apparently came into use as indicated by larger quantities of the bones of small fish and small terrestrial-aquatic animals to appear in shell middens. They apparently lived a seasonally relocated life including spending some of their time inland on the periphery of agricultural tribes. Although Mossy Grove peoples are not known to have practiced agriculture themselves, they may have bartered for produce.

According to Dr. Dyer and other sources, Mossy Grove peoples had some watercraft for use in streams, lakes, and estuaries but not, so far as is known, for excursions far into the Gulf. Indeed, only one dugout canoe, now in the Bullock Texas State History Museum in Austin, has been reported found near Mossy Grove territory—on the lower Brazos River. It is counter-intuitive to think native peoples living in a riverine-estuarine environment did not make extensive use of watercraft—surely they did, or did they? Mossy Grove archeological sites have yielded few heavy stone or shell tools, such as axes and adzes that would be suitable for crafting a dugout canoe or other major woodworking. At present it may be assumed that there was limited watercraft use, but future research may tell us otherwise.

Insofar as it can be recognized at present, the Mossy Grove Tradition was reminiscent of early Woodland cultures, particularly those of the lower Mississippi Valley. Their earthenware usually was soft-fired sandy clay (most named Goose Creek wares) or fine clay (named Tchefuncte, Baytown or San Jacinto wares) often with the addition of either sand or small fragments of broken pots to minimize shrinkage of the earthenware when it was being fired. The shapes of their pottery vessels were usually spherical or cylindrical jars and bowls rarely decorated and then mainly by rudely executed geometric incising made with a sharp tool or, occasionally, by impressions of twine or shells. Some sites contain examples of ornamented earthenware that owes their origin to interaction of some sort—possibly trade—with groups living either near the lower reaches of the Mississippi River or in northeast Texas. As pointed out over a half century ago by pioneer Texas coastal archeologist T. N. Campbell, pottery identical to or reminiscent of that seen in those latter areas and dating as far as 2000 years ago, while not abundant, is commonly found in early Mossy Grove sites.

The lithic assemblages had limited variety in tool types and other rudimentary Mossy Grove tools and ornaments were made of stone, bone, and shell. There likely were recognized territories through which people moved at various times of year often to take advantage of seasonal availability of resources when they hunted, fished, and gathered plant products for food and materials.

While most of their ceremonial activities are not evident in artifact collections, mortuary ritual seems to have been simple with burials often in habitation sites no longer in use. In some locations, small earthen platforms were used for burial that may have devolved from the conical mortuary mounds so common in the eastern United States and found as near to the coastal Sabine area as the Jonas Short site in San Augustine County, Texas, the Coral Snake site in Sabine Parish, Louisiana, and the Lafayette mounds of south Louisiana.

We may also note several elements of Southeastern Woodland cultures that are not present in the Mossy Grove Tradition but can be seen in cultures directly to the north and east of the Mossy Grove territory. These would include gardening and agriculture; large platform mounds and ceremonial centers; villages with moderately large sedentary populations; and manufacture of many artistic objects in clay, stone, bone, or shell. The most consistent material culture reflections from elsewhere appearing in Mossy Grove sites were small numbers of ceramics either from or that imitated those of the Lower Mississippi Valley and of the Caddo area.

The Mossy Grove concept provides a distinctive culture-geographic term labeling the late prehistoric cultures of coastal southeast Texas and southwest Louisiana in a manner similar to how other culture areas nearby are distinguished such as the Western Gulf Tradition, Caddo area, and Lower Mississippi Valley.

But the cultural roots of the Mossy Grove Tradition may run deeper than the Late Prehistoric, and farther off as well. A quarter of a century ago, Texas archeologist Harry Shafer studied early lithic artifacts from east Texas and concluded that if one looks at the complete technological assemblages rather than just diagnostic projectile points, it seemed that Paleo-Indian and early Archaic lithic assemblages of eastern Texas reflected hunting and gathering adaptations to resources and habitats more characteristic of the eastern woodlands than of classic big game hunters. This also was a conclusion reached in investigations of early sites in nearby Wharton County, Texas.

But even when not looking so far afield, eastern affiliations may be evident. Recent study by archeologist Melanie Stright and her team of the large collections of Paleo-Indian and Archaic lithic tools thrown up by waves on to the Gulf beach near Sabine Pass also concluded that the technology of diagnostic Paleo-Indian projectile points distinctively resembled similarly aged artifacts from the eastern United States rather than those of the west. It should be remembered also that the early sites from which these diagnostic points were eroded would not have been formed originally by habitation in coastal landscapes but rather were interior riverine and upland prairie terrains that were inundated and buried by post-glacial rising sea level.

And so it may be that in time research will show the origins of the Mossy Grove ethnic groups, and perhaps of their Archaic and Paleo-Indian ancestors, derive largely from prehistoric cultures of the interior southeastern United States. Although ancestral connections for the earliest prehistoric periods remain to be demonstrated, the Mossy Grove cultures of central and southern east Texas had much in common with the more recent Woodland cultures of the southeastern U.S.

Contributed by Lawrence E. Aten and Charles N. Bollich.

Sources:

Aten, Lawrence E.

1983 Indians of the Upper Texas Coast. Academic Press, New York

1984 Woodland Cultures of the Texas Coast. In Perspectives on Gulf Coast Archaeology, edited by D. Davis, pp. 72-93. University Presses of Florida, Gainesville.

Aten, Lawrence E. and Charles N. Bollich

2002 Late Holocene Settlement in the Taylor Bayou Drainage Basin: Test Excavations at the Gaulding Site (41JF27), Jefferson County, Texas.

Studies in Archeology 40, Texas Archeological Research Laboratory and Special Publication No. 4, Texas Archeological Society.

Dyer, J. O.

1917 The Lake Charles Atakapas (cannibals): period of 1817-1820. Galveston, privately printed.

Stright, Melanie J., Eileen M. Lear, and James F. Bennett

1999 Spatial Data Analysis of Artifacts Redeposited by Coastal Erosion: A Case Study of McFaddin Beach, Texas. Minerals Management Service OCS Study MMS 99-0068, 2 volumes. Herndon.

Story, Dee Ann

1990 Cultural History of the Native Americans. In The Archeology and Bioarcheology of the Gulf Coastal Plain, by D.A. Story, J.A. Guy, B.A. Burnett, M. D. Freeman, J. C. Rose, D. G. Steele, B. W. Olive, and K. J. Reinhard, pp. 163-366. Research Series No. 38, vol. 1, Arkansas Archeological Survey, Fayetteville.

Atakapan man during the early historic era, as envisioned by artist Frank Weir.

|

|