Shellfish

Shellfish were a ubiquitous resource that the coastal natives exploited in a variety of ways. The two main categories of shellfish are bivalves and gastropods. As salinity levels changed over time, shellfish populations would have changed in frequency. Bivalves such as clams, oysters, and scallops prefer a lower salinity level and reside in bays or at the confluence of bays and rivers. Gastropods (whelks and conchs) prefer the more saline environments of tidal passes near the Gulf of Mexico. As the barrier islands formed over time (completed around ca. 2800 B.P.), salinity levels gradually decreased. As a result, gastropods appear more often in earlier, Archaic contexts than in Late Prehistoric contexts. Marine crustaceans such as the rock crab and blue crab have also been recovered from archeological contexts. However, throughout time deeply stratified shell middens—typically of oyster—are a hallmark feature of coastal sites.

Along the Texas coast shellfish were utilized as food, tools, and ornamentation. Native peoples sought a variety of bivalves—Rangia cuneata, Rangia flexuosa, eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica), southern quahog (Mercenaria mercenaria), and sunray venus (Macrocallista nimbosa)—and gastropods—lightning whelk (Busycon perversum pulleyi), banded tulip (Fasciolaria hunteria), Florida horse conch (Pleuroploca gigantean), and sharkeye (Neverita duplicate). Along the upper Texas coast the common rangia and eastern oyster were utilized as a food source; along the central and south a wider variety of mollusks were exploited. Like fish, shellfish were more easily harvested in particular seasons. Rangia accrete growth rings at different rates according to the season. By analyzing these accretion rates, arcaeologists have determined Rangia were most intensively harvested between mid-April and late July. Since shellfish provided little meat, a large amount of shellfish consumption was needed to make a significant impact on caloric uptake. Archeological evidence from the Lower Lavaca River in Jackson County suggests shellfish were steamed in shell-lined hearths.

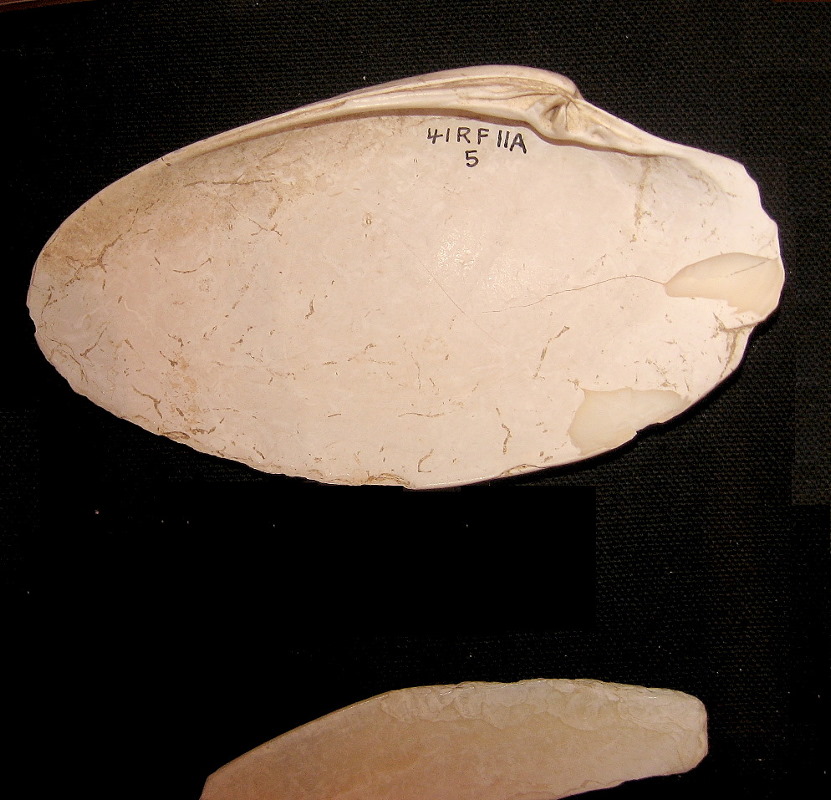

Due to the absence of lithic resources along the Texas coast, shellfish also served a utilitarian function. The shell of the lightning whelk was modified into a variety of tools. For example, the columella could be manipulated into a gouge or chisel for woodworking, a billet for working shellfish or chipping stone, and wedges or picks used in oyster extraction. Some sites on the lower coast even produced projectile points made from columellas. Additionally, the outer shell, or whorl, was often worked into an adze possibly for woodworking. Oyster shell found at site 41SP120 may have been modified for use as hoes by puncturing a hole near the valve hinge. This would have enabled them to be hafted to a stick using asphaltum or cording, making them excellent digging tools to harvest aquatic roots or other plants. Tools made from Sunray venus clams have been found at several sites, such as 41RF11. These specimens exhibit edge-modification suggesting use as scrapers or filet knives. With only limited sources of stone available for tools, coastal hunter-gatherers adapted and utilized their environment to the fullest extent.

Lightning whelk (Busycon perversum pulleyi), Olivella, and Oliva were heavily used for art and ornamentation. Large blanks cut from whelk exterior shell were cut and incised to make a pendant, or gorget, that could be worn on the chest Olivella and Oliva were strung into elaborate necklaces and perhaps traded for needed items; bivalves such as mussels and clams also were worked into “tinklers” and worn as decorative accouterments.

|

|

|

|