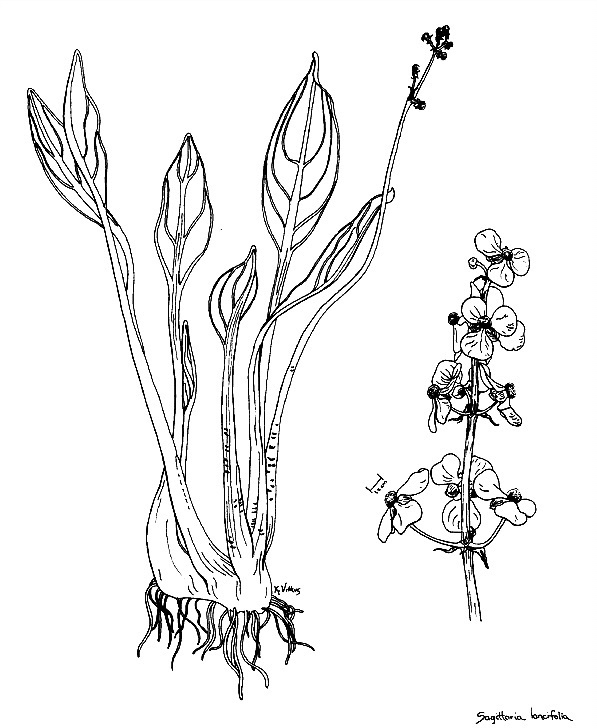

Arrowhead Root, Wapato

Sagittaria spp.

Alismataceae Water Plantain Family

Arrowhead root is a perennial aquatic plant with very showy, long, arrow-shaped to elliptical leaves, hence the name arrowhead. Many of the species form food-storing tubers that provide a source of food and medicine. These plants grow in standing water and marshes in many areas along the Texas coast and throughout North America. Nine species of arrowhead are recorded in Texas (Correll and Johnston 1970), and about eight of these have been collected along the Texas coastal plains. Arrowheads are often grown in aquatic gardens because of the large, attractive leaves. These leaves are easy to spot in a marshy area, and the plant can grow in dense stands, both ideal qualities for a potential wild food crop.

Was arrowhead one of the root foods collected by the indigenes that Cabeza de Vaca lived with and observed? This is an intriguing possibility. In the TBH exhibit “Learning from Cabeza de Vaca”, Alston Thoms speculates that arrowhead was one indeed of the foods that the coastal natives collected during the winter months. The description of the tuber as resembling a truffle is certainly a close fit. Unfortunately, we have no specific descriptions or references to the use of arrowhead root in our state. The widespread records of arrowhead use, however, suggest that humans took advantage of this resource wherever it grew in sufficient abundance.

Archeology. Arrowhead has not been conclusively identified in archeological sites. This is very likely due to the difficulty of recovering and identifying tubers in archeological sites with poor preservation of plant remains.

Food. Ethnographic references to the most common species on the Texas coast are not available. The most frequently discussed species is Sagittaria latifolia, which is widely distributed across North America but is listed as rare in Texas, and is confined to the eastern part of the state (Correll and Johnston 1970). The one species that is listed for the coastal bend area of Texas, Sagittaria lancifolia, has a single ethnobotanical reference that I could locate (Jones 1975; Sturtevant 1954). A third species, Sagittaria cuneata, grows widely across North America and the greater southwestern region, but in Texas is confined to the high plains.

Despite the lack of species-specific information, the species of arrowleaf growing on the Texas coastal plain can form edible tubers. For this reason I will discuss some of the uses and preparation methods gleaned from ethnobotanical observations.

The tubers of Sagittaria latifolia were used by several Missouri River tribes for food, including the Dakota, Omaha-Ponca, Pawnee, and Winnebago. The tubers were collected and either roasted or boiled (Gilmore 1977: 13). Gilmore (1977:13) also quotes an 18th century description of its use among the Algonquians in which is was boiled or roasted on hot ashes (more likely coals). The Lakota also consumed arrowhead tubers. In fact, the plant appears on the cover of a book that summarizes a valuable ethnobotanical collection made in the 1920's in the Rosebud, South Dakota area by Father Eugene Buechel's (Rogers 1980). Father Beuchel collected plants, interviewed informants, and recorded Lakota names and uses for each plant.

In the upper Midwest, the Chippewa collected and dried the arrowhead tuber. It was then boiled and used for food (Densmore 1928: 319). Arrowhead was also used by groups in the desert southwest. The Cocopa baked, peeled, and mashed the tubers. The Cocopa record is an intriguing, but not detailed description of baking instead of boiling or roasting the tuber (Castetter and Bell 1951: 207; Kelly 1977). Palmer (1878:600) noted that the Mojave waited for the flood waters of the Colorado River to subside before conducting a spring harvest of arrowhead (noted as Sagittaria simplex), and that the tasty root had a mealy or farinaceous texture. To the north, the Pomo also utilized the tubers for food (Barrett 1952).

An excellent first-hand account of collecting arrowhead is reported by John Kallas in an issue of Wilderness Way (2003). He describes his first-hand experience of harvesting arrowleaf in waist deep water in November (in Washington state). One uses the feet to work the mud or muck to loosen the tubers for harvesting. This is the work of a hardy soul (Kallas 2003). He used the method described by Lewis and Clark during their early 19th century trek across the middle of the continent. Kallas (2003) reports gathering almost 2 pounds of tubers in 15 minutes from an area measuring 2.5 square yards.

Kallas (2003) notes that the tubers grow on the tips of underground stems termed rhizomes, and that each tuber is capable of producing new plants. Each tuber is oblong and can be irregular in shape, about 0.75-2.0 inches long and 0.75-1.75 inches wide. He compares the taste to that of an Idaho potato with a slightly bitter aftertaste. Although the tubers are described in detail, the article does not describe how they were prepared.

Medicine. There are a few cryptic notes regarding the use of arrowhead as medicine. The Lakota of Rosebud used it for an unspecified medicinal application (Rogers 1980). Densmore (1928: 319) notes that the Chippewa used an infusion of the root to settle indigestion. The Navajo used the plant for headaches (Elmore 1944:24). Huron Smith notes that the Ojibwa ate the tubers (cited as corms) for indigestion and that they also administered the same to horses (1932)

References

Barret, S. A.

1952 Material Aspects of Pomo Culture: Part One. Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee 20:1-260.

Castetter, E.F, and Willis H.Bell

1951 Yuman Indian Agriculture. Albuquerque. University of New Mexico Press.

Correll, D. and M. C. Johnston

1970 Manual of the Vascular Plants of Texas. Contributions from the Texas Research Foundation, Volume 6. Renner, Texas.

Densmore, Francis

1928 Uses of Plants by the Chippewa Indians. Forty-fourth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 1919

Elmore, F. H.

1944 Ethnobotany of the Navajo. University of New Mexico Bulletin. Monograph Series 1(7). University of New Mexico Press. Albuquerque.

Gilmore, Melvin R.

1913 A Study in the Ethnobotany of the Omaha Indians. Nebraska State Historical Society 17:354-357.

1977 Uses of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region. University of Nebraska Press. Lincoln. [Reprint of original Thirty-third Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 1919].

Jones, Fred B.

1975 Flora of the Texas Coastal Bend. Welder Wildlife Foundation. Sinton, Texas.

Kallas, John.

2003 Wapato: Indian Potato. Wilderness Way Magazine. 9(1): 27-31.

Kelly, William H.

1977 Cocopa Ethnography. Anthropological Papers of the University of Arizona No. 29. Tucson, Arizona.

Palmer, E.

1878 Plants Used by the Indians of the United States. American Naturalist 12: 593-606; 646-655.

Rogers, Dilwyn

1980 Lakota Names and Uses of Native Plants. Buechel Memorial Lakota Museum. St. Francis, South Dakota.

Smith, Huron

1932 Ethnobotany of the Ojibwe Indians. Bulletin of the Public Museum of Milwaukee 4:327-525.

Sturtevant, William

1954 The Mikasuki Seminole: Medical Beliefs and Practices. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation. Yale University. New Haven, Connecticut.