Kirchmeyer Site

The Kirchmeyer Site (41NU11) is located on the southwestern shore of Oso Bay at the confluence of Oso Creek in Nueces County, approximately 4 miles south of the Corpus Christi Bay shoreline. Evidence from the site spans the period A.D. 1200-1900. Represented are occupations of the Late Prehistoric period—including a major Rockport phase component likely attributable to Karankawa groups—and much of the Historic period, including possible traces of Zachary Taylor's army in the 1840s.

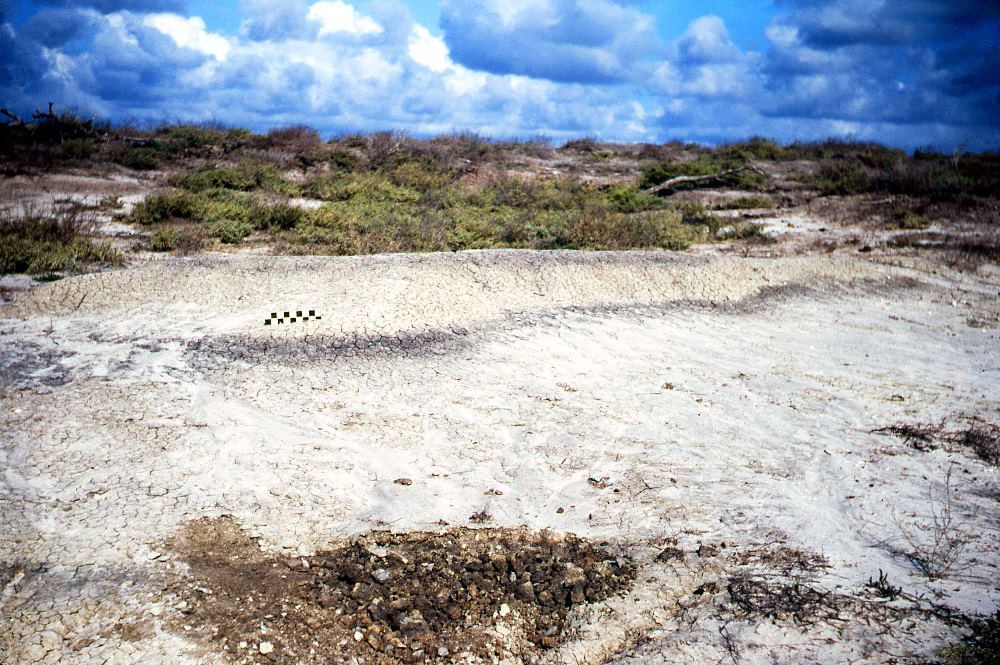

Spanning some 10,000 square meters, the site is situated within a scrub brush thicket on and within an eroded sand and clay dune, a somewhat common feature on the central Texas coastline. Rising 15-25 feet (5-8 meters) above mean sea level, the dune would have offered an elevational advantage on the otherwise flat coastal environment, as well as a compact surface on which to camp, cook, and make tools. The dune itself dates only to the last 4000 years or less; clay dunes in the area did not form until coastlines had stabilized and the barrier islands formed during the Holocene (ca. 4000-2500 B.P.).

For occupants at the site, procuring fresh water would have been a concern. The nearest potable water is in Oso Creek, about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) to the south. A nearby pond contains water intermittently, but this feature may not have been present in prehistoric times.

Archeological Investigations

Erosion of the dunes over time exposed numerous artifacts throughout the area, attracting the attention of collectors. Both avocational and professional archeologists worked at the site to salvage information, particularly as the urban expansion of Corpus Christi threatened to encompass the area. Both avocational archeologist George C. Martin and University of Texas archeologist A. T. Jackson may have visited the site in the 1920s, and W. A. Price began work in the 1930s, recovering a variety of prehistoric and historic materials.

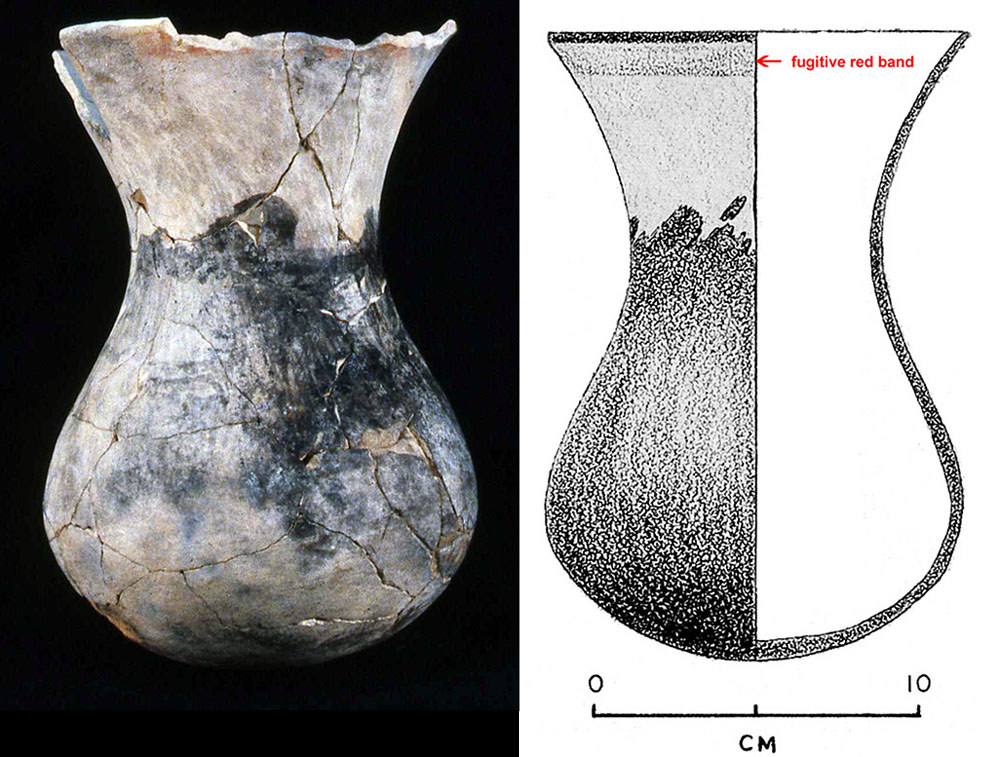

More systematic work was begun in the 1960s by Cecil Calhoun, who attempted to recover what may have been an historic Indian component at the site. Calhoun and Dee Ann Story, then Curator of Anthropology at the Texas Memorial Museum in Austin, discovered a cluster of unusual, native-made ceramic sherds eroding out of a dark-stained, occupational zone in a gully. Although two additional sherds were found in a dark-stained layer nearby, no other diagnostic artifacts were recovered. Later refitted to form a complete polychrome Rockport vessel, the sherds were a highly unusual find.

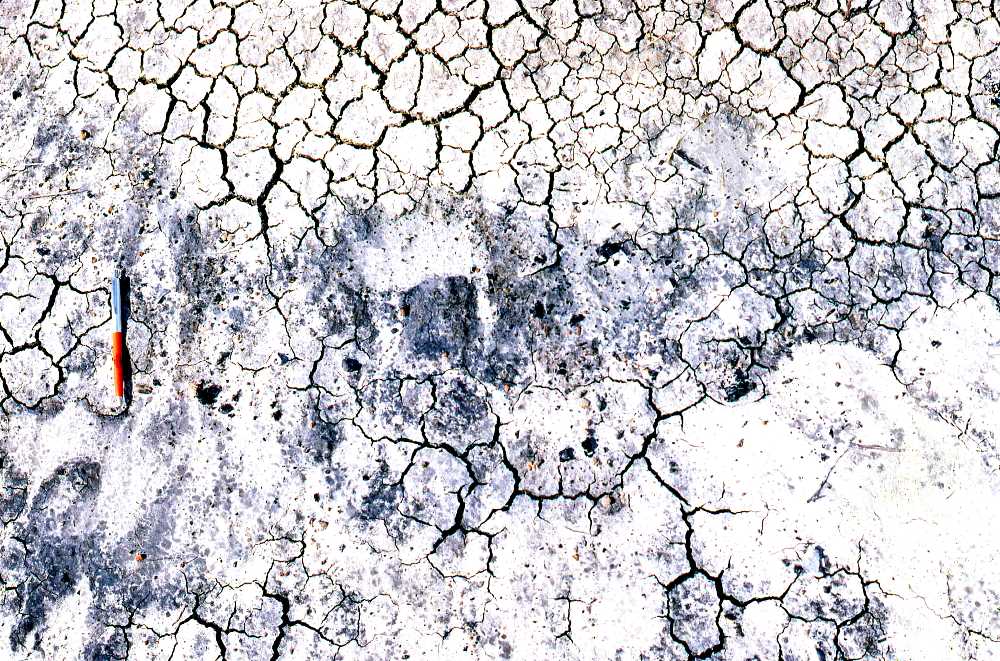

Test units placed roughly 10.5 meters (35 feet) away, in similar dark-stained soil, revealed a shallow, basin-shaped hearth with fragments of a European bronze bell, along with a section of a large Rockport Black-on-Gray olla, flint chips, marine shells, and animal bones. Charcoal from the hearth, submitted for radiocarbon assay, returned a calibrated date of A.D. 1436-1635, clearly pertaining to what is termed the Contact, or early Historic, period.

Encouraged by this discovery, Thomas R. Hester and James E. Corbin, then students in the Anthropology program at the University of Texas at Austin, returned to test the site further in 1969. Excavations were hindered by the hard-packed clay dune deposits. Most of the materials recovered were from the upper 75 cm (2.5 feet), primarily from the eroded surface of the dune. These included an array of faunal remains—shellfish (whelk, sunray venus clams, oyster), fish (chiefly black drum), and mammal (both deer and bison) bones. An extensive and well-documented surface collection by Jerry Bauman also was made and is in the TARL collection. Archeologist Robert Ricklis also investigated the site in 1987. Among items recovered, the most significant were a number of fish otoliths, which were analyzed for seasonality. Although the sample was small (11 specimens), the analysis showed pronounced usage of the site in the winter months (9 specimens; 82%).

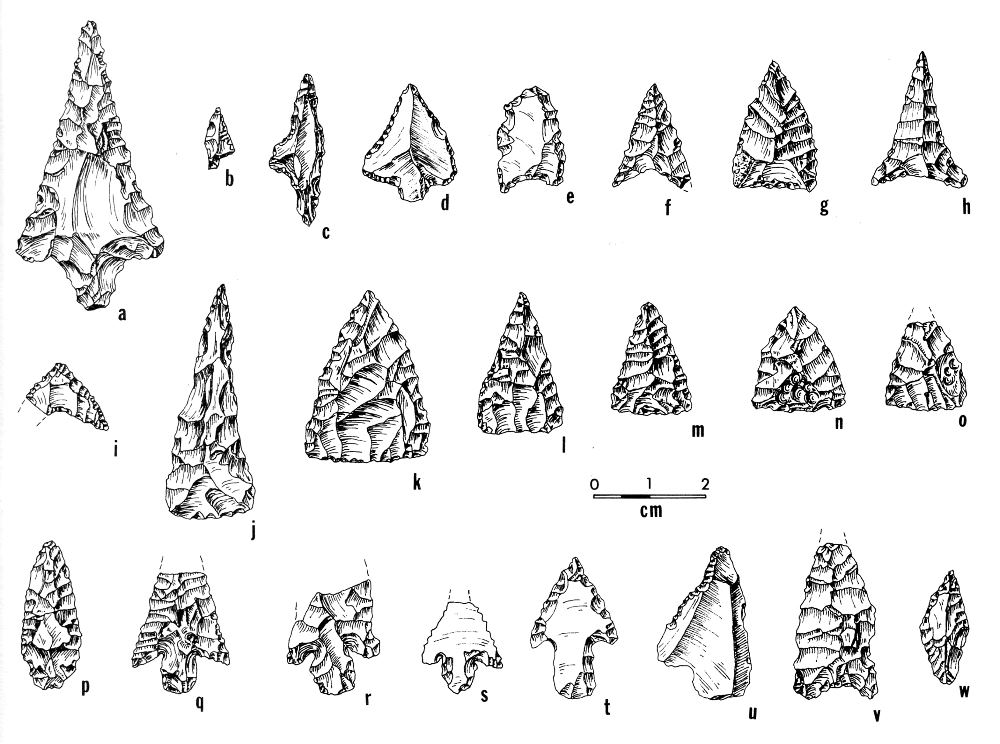

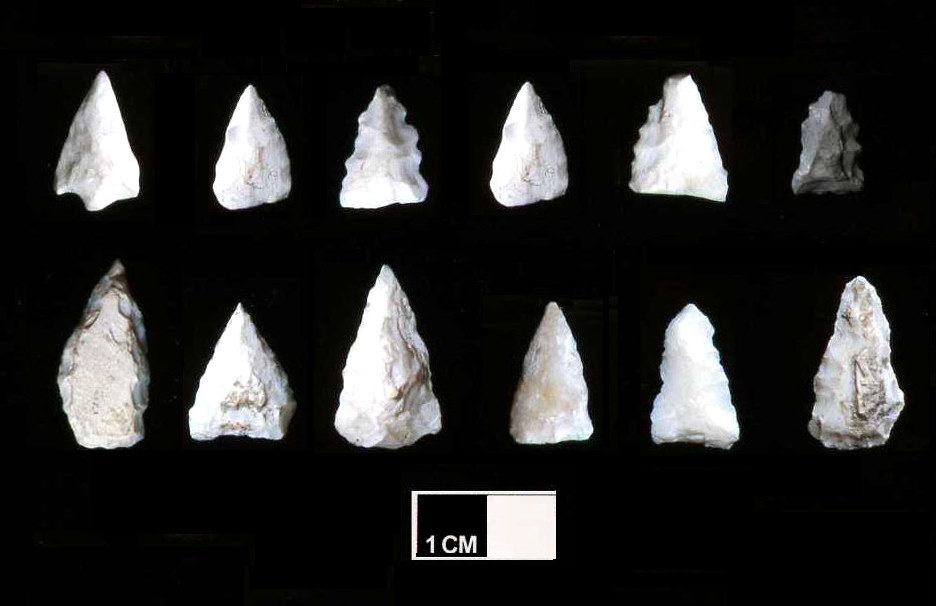

The Late Prehistoric use of the site was probably a long but intermittent one, with groups coming back to the site season after season over hundreds of years. This is evidenced by a variety of camp materials and debris including tools, weapons, and pottery. In the Kirchmeyer collections there are eight types of arrowpoints represented, two of which, the Padre and the Lozenge, are restricted to Padre Island and the central part of the Texas coast. The other six types, Perdiz, Starr, Fresno, Cameron, Bulbar Stemmed and Guerrero, were used across a broader area. Guerrero points are linked to the Spanish Colonial mission period. Bulbar Stemmed points also have been associated with incised Rockport ceramics, which also were found at the site.

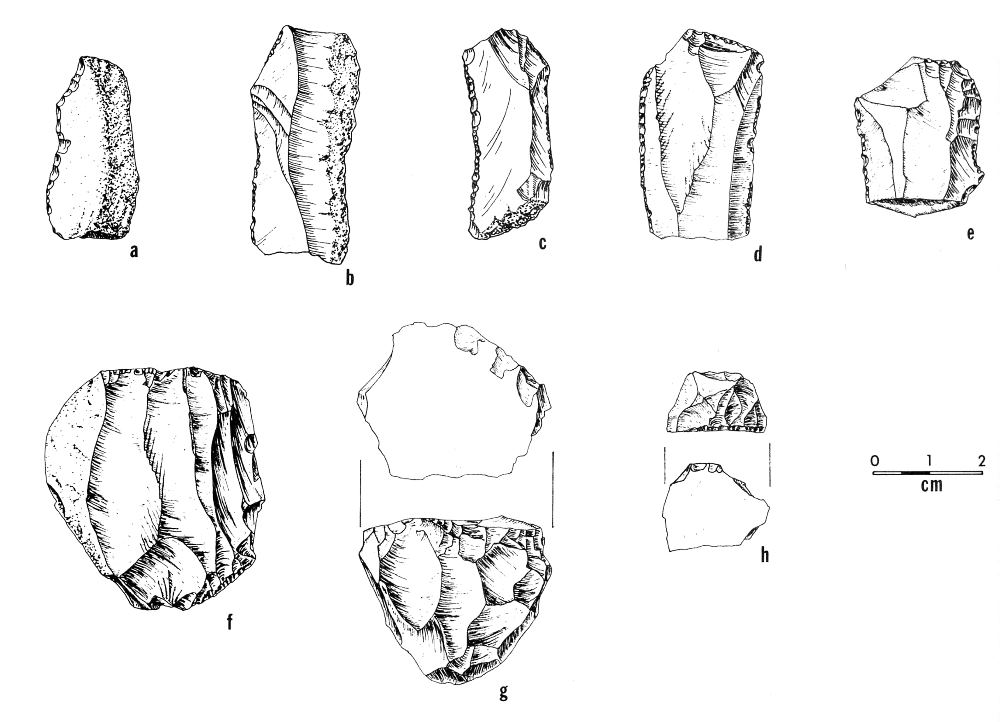

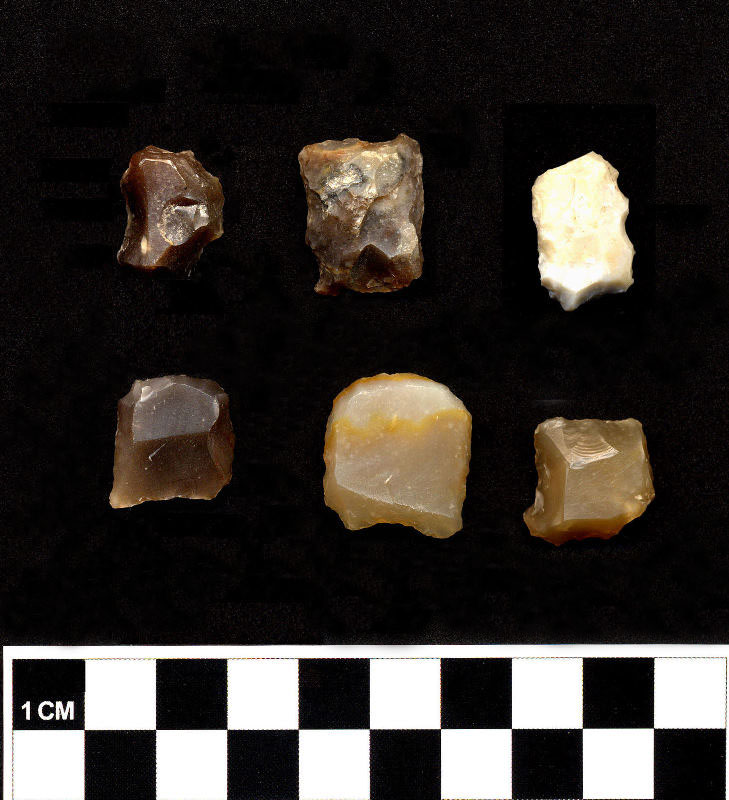

Also present are chert pieces representative of a Late Prehistoric blade technology as well as utilized, or modified, debitage (12% of the entire debitage recovered). This percentage is interesting when contrasted with other coastal sites far from lithic sources; most of these sites contained very large percentages of modified flakes. At Kirchmeyer the relative scarcity of modified flakes suggests shell (an abundant resource) was used in place of stone when feasible. Other native artifacts recovered from the site were antler tine segments, one of which was painted with a wavy black design, bone awl fragments, and pumice abraders.

Marine shells also make up an important component of the recovered material, indicating a reliance on shell fish. Sunray clam is predominant among the represented species. The artifact types range from shell tools and weapons (small projectile points, scrapers, adzes, awls) to ornaments (bead preforms and a freshwater mussel pendant).

Rockport Ceramics

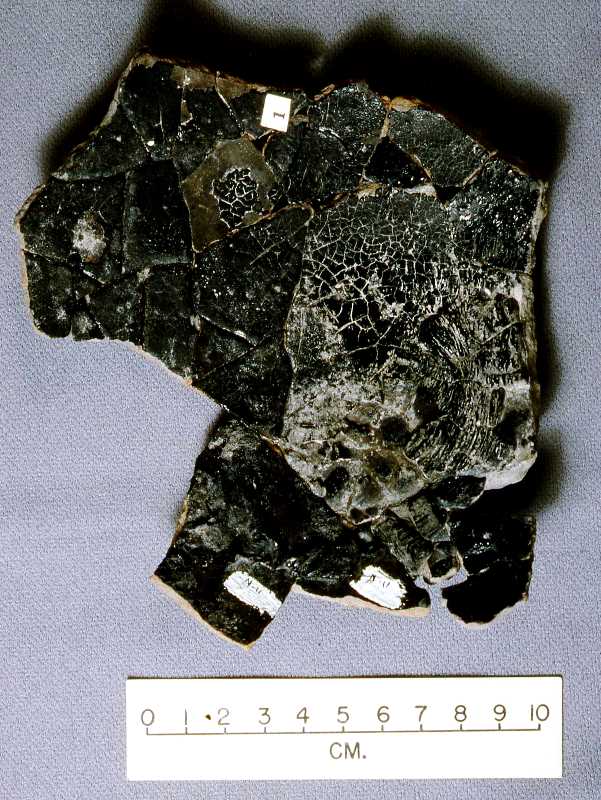

By far the largest portion of recovered prehistoric material was ceramic sherds, 12,628 in all. Represented in this collection are the three established Rockport types: Plain, Black-on-Gray and Incised, as well as a single extremely rare Rockport Polychrome jar.

The Rockport ceramics were made of sandy-paste clays usually with either bone or shell temper and probably of coiled construction. The small size of the sherds is a function of the sandy clay matrix and probable low-firing temperatures, which made the resultant ceramics extremely friable. What appears to be crushed shell temper may be incidental, occurring naturally in the lagunal clay sources from the surrounding coastal clay dunes. Nearly 40% of the sherds evidenced bone temper. A few (4%) had been painted with asphaltum to create black wavy lines and dots but, because of the small size of the sherds (averaging only .5 gram each), no overall design or pattern could be discerned

Vessels with painted decorations, as well as some punctation and incising, are typical of the Rockport ceramic tradition. Much more rare is the use of more than one color in painted decoration, as evidenced in the small polychrome Rockport jar discovered at the site by Calhoun. Measuring 18.9 cm high (7.4 inches) the vessel is globular in shape with a constricted neck (7.4 cm) and widely flared rim (incomplete, but estimated to have had a maximum diameter of 12.8 cm. It was made of light-colored clay, tempered with sand, apparently using the coil technique. A black band of asphaltum was painted around the rim, and beneath this, a thin band of reddish color, which has faded to brown. Asphaltum also was thinly applied to the exterior surfaces and more thickly to the interior, presumably to waterproof the vessel.

As Calhoun noted, “By far, the most outstanding feature of the vessel is the combined use of asphaltum and a fugitive red wash, which intentionally or accidentally has produced a polychrome decoration.” U.T. anthropologist T. N. Campbell, who speculated about the possibility of a polychrome tradition in the Rockport focus, suggested the possibility of Spanish influence.

Asphaltum is a natural black tar occuring all along the Gulf Coast of Texas in seeps and clumps. native potters used asphaltum for painting decorations on vessels and to mend broken pots. Asphaltum also was used to coat and seal the interiors of certain large pots, rendering them essentially watertight. Such vessels could be used to store and transport water from location to location, a critical function since potable water was in scarce supply along this portion of the central Texas coast. Vessels without asphaltum coating likely were used for storage of dry foods.

Historic Occupations

Thousands of artifacts from the Historic period also were recovered at the Kirchmeyer Site. Of these, a small number pertain to the early Historic, or Contact, period. These early pieces include two European pipe fragments, a handful of glass trade beads, brass tinklers, and a bronze bell fragment. The last artifact is the upper, or cannon portion, of a bell plus a very small segment possibly of the sound bow. These were recovered from the lower portion of a hearth feature discovered by Cecil Calhoun. Charcoal from this feature returned a radiocarbon date range (calibrated) of A.D. 1436-1635.

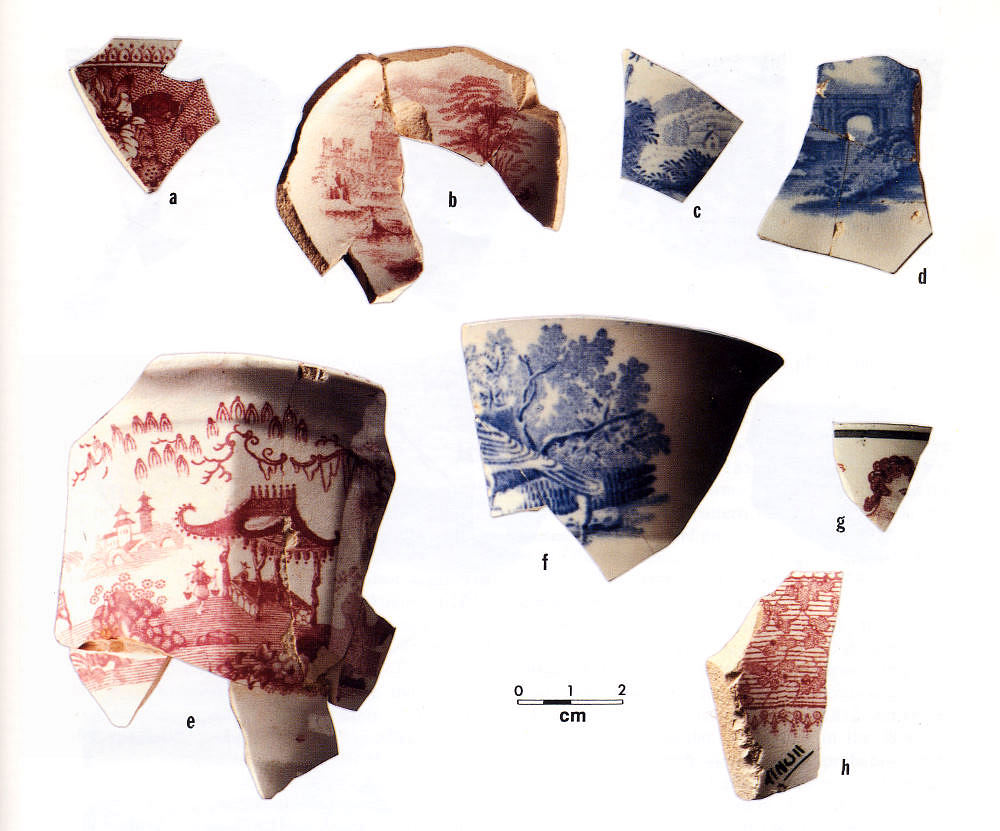

Later, more extensive use of the site is evidenced by gunflints, military objects such as brass uniform buttons, bottle glass, and a colorful array of European ceramic sherds. These ceramics include both refined earthenwares—British transfer-printed, handpainted, banded slipware, shell-edged, etc. —and a lesser quantity of utilitarian stonewares and Mexican redwares. Because of the preponderence of European earthenwares (72%), it was assumed that the site was not much influenced by a Spanish Colonial presence.

The historic artifacts at the site point to a rather large accumulation of refuse over a relatively short span of time. Most of the ceramics as well as the glass artifacts, although dated only relatively according to decorative motif and improvements in the technology of glassmaking, seem to cluster around the middle of the 19th century. Curiously, no utilitarian kitchenware was identified, except for a few pieces of stoneware. Most of the ceramics, in fact, represent rather fine tableware.

Life at the Clay Dune

The Kirchmeyer site was a campsite visited periodically during the Late Prehistoric period, A.D. 1200-1700. The ceramics indicate a people who were not sedentary but rather campers who trekked seasonally up and down the coast, and onto the inland prairies, in search of game and other resources. For the most part, they would have been reliant on canoes for longer journeys along the intercoastal waterways and marshes.

During the early Historic period, native coastal peoples may have traded with European explorers coming into their lands or salvaged materials from shipwrecks. Several vessels are known to have wrecked on the nearby barrier island. Later people used this site as well. Although no evidence of a structure was found, the large quantities of refuse—tableware, bottles, and metal objects—suggests there must have been a domicile or several structures nearby. Archival records and early maps, however, provide no indication of residences in the area. Some of the artifacts—specifically, the many types of fine ceramics, coupled with the 13 gunflints, uniform buttons, and other military objects—raise another possibility.

In 1845, General Zachary Taylor, with an army of 3,860 men, encamped at the small village which is now Corpus Christi (known at the time as Fort Marcy). Taylor had been ordered to the area to help defend Texas from a potential Mexican attack. Among his regiments was the 2nd Dragoons. In 1846, President Polk ordered Taylor to march to the Rio Grande and build a fort as a show of force to the Mexicans. The Kirchmeyer site may have been a trash dump left by the departing army. One of the brass buttons found at the site bore the 2nd Dragoon insignia, an eagle marked with the letter "D."

The value of the Kirchmeyer collection is in the wide variety of artifact types which typify the coastal lifestyle during the Late Prehistoric period—a hard-scrabble existence where every resource was utilized, no matter how small in size, where materials such as asphaltum were put to use to coat or mend the rather crude pottery, and where something as foreign as a brass bell could capture the imagination of a native coastal dweller. The more recent Historic period artifacts offer a fascinating glimpse of the varied and often fine objects used on the early frontier in south Texas.

Contributed by Pam Headrick and TBH editor Susan Dial.

Sources

Calhoun, Cecil

1964 A Polychrome Vessel from the Texas Coastal Bend. Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society 35: 205-211.

Headrick, Pamela J.

1993 The Archeology of 41NU11, the Kirchmeyer Site, Nueces, County, Texas: Long-Term Utilization of a Clay Dune. Studies in Archeology 15, TARL, the University of Texas at Austin.

Huffman, G. G. and W. A. Price

1949 Clay Dune Formation near Corpus Christi. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology 19(3): 118-127.

Pierce, G. S.

1969 Texas Under Arms: The Camps, Posts, Forts and Military Towns of the Republic of Texas 1836-1846. Encino Press, Austin.

Handbook of Texas: Zachary Taylor

![]()

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|