The Bosque River Basin and Beyond

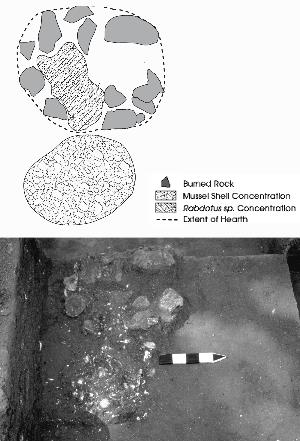

The hunting and intense processing of ungulates, primarily deer, was a major endeavor during nearly all time periods at all three sites. In addition to harvesting the meat, campers crushed and cooked the bones to recover fat and marrow, as evidenced by large quantities of spirally fractured remains. Both the McMillan and Higginbotham sites also provide evidence, in the form of burned rock middens, basin-shaped hearths, and macrobotanical remains, that an intense level of plant processing and consumption was part of the subsistence strategy as well. These foods were primarily geophytes, plants with underground bulbs, roots, and tubers. We speculate that the prime season for harvesting geophytes was in the spring. During this time, small family groups would have banded together to harvest and process the food in bulk. Evidence for lengthier periods of stay needed to accomplish these tasks is indicated by the structure and layout of these sites at certain periods, such as greater distance between features and use of refuse piles for dumping trash.

In addition, the Bosque River people’s diet was augmented through the hunting, trapping, and collecting of smaller animals and mussels, particularly when site occupations were lengthy and acquisition of high-ranked resources such as deer likely became cost prohibitive. Mobility was key to providing access to these resources, some of which were dense enough or available at sufficiently low cost that foraging could take place in relatively small areas, supporting short movements (distances) between camps, and at times lengthy stays at camps. This nomadic lifestyle required these hunters and gatherers to possess and employ technologies that were simple and transportable, yet durable and functional.

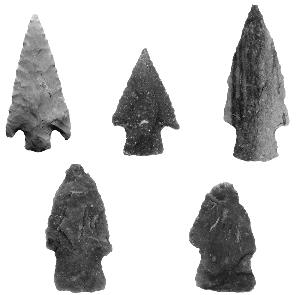

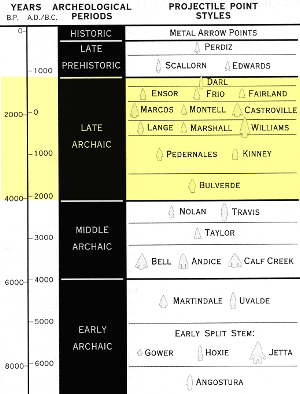

Based on the materials recovered from the excavations, the technologies used to acquire and process these resources largely remained unchanged until the Late Prehistoric period, when arrow points replaced dart points, and ceramic pottery was added somewhat later. For the most part, tool kits consisted of bifacial tools, which provided durable working edges that were amenable to multiple cycles of resharpening and easily transported from site to site. Expedient flake tools were at times employed to accomplish simple cutting and scraping tasks, which would have conserved the working edges of the formal bifacial tools, something that was particularly important in the absence of locally available and suitable lithic materials. Intensive use of formal tools is evidenced by heavily resharpened dart points and other bifacial tools at all of the sites. The evidence suggests that many formal tools were brought to the sites as late-stage and finished specimens. Onsite knapping activities suggest tool maintenance and refurbishing occurred at all of the sites, with the primary reduction of raw materials occurring in a limited fashion only at the McMillan site.

Another critical resource for the prehistoric campers was fuelwood. Choice of woods used at different times provides some insight into length of stay at the camps and, in fact, may have been the determining factor in camp location. Most of the recovered charred wood was from self-pruning trees, such as oak and pecan, indicating a good supply of fallen or dead wood was available during most of the occupations at the Bosque River camps. However, a somewhat different picture was revealed at the McMillan site. There, large amounts of charred wood from possumhaw/yaupon trees were found, indicating these small trees had been purposely cut for firewood, likely after nearby fallen limb wood had been used up or become too difficult to acquire. Further, since McMillan campers had consumed all of the easily accessible dead limb wood, their occupations may have been relatively lengthy.

To a large extent, we believe the location of camps was determined by women, as they carried the critical role of gathering firewood and plant foods. They would have chosen a spot where useful plants were most dense, and where easily obtained firewood was prevalent. Moving a camp was hard work, and for this reason, the campers would have selected a spot with a good supply of resources, such as dense patches of geophytes. Once foods were depleted and fuelwood exhausted, campers would have had to make the decision to move to another locale or expend more energy obtaining less easily obtainable resources.

Overall, the picture presented at these sites is one of a successful hunting and gathering way of life that remained virtually unchanged for nearly 5,000 years in the North Bosque River valley.

Waco Lake and Central Texas Archeology

Researchers have traditionally considered the Waco area as part of the central Texas archeological region, although it actually is on the periphery of this region. The archeological record and projectile point style sequences are a testament to this, as they contain elements that suggest influences and contacts to varying degrees over time with areas to the east and northeast. The Late Archaic dart points and Late Prehistoric ceramics from the Britton, McMillan, and Higginbotham sites fit this pattern well. Many of the dart points may be thought of as traditional central Texas styles, such as Darl, Ensor, Castroville, Marshall, Pedernales, and Bulverde. Missing from this list of Late Archaic styles, however, are some types that are quite common to central Texas, such as Fairland, Frio, Marcos, Montell, and Williams. Some of these styles may have more local or restricted distributions throughout the central Texas region, which may explain their absence from the Waco Lake assemblages.

Dart point styles in the Waco Lake assemblages with distributions that are peripheral to or primarily east and northeast of the central Texas archeological region include Dawson, Gary, Godley, and Kent. It is interesting to note that these styles, particularly Godley which is so prevalent at the Britton and McMillan sites, are absent or nearly absent from the rockshelters in the nearby Hog Creek basin. This suggests that the groups who used these point styles, particularly Godley points, were not involved in the predominant settlement-subsistence system and therefore were outsiders, either intruders or invited guests, or maybe both, who foraged in the lower Bosque basin at certain times of the year. This leaves the groups who used Ensor, Darl, and other more traditional central Texas point styles, which are present at all site types, as the local participants in the lower Bosque basin Late Archaic settlement-subsistence system. This suggests that the Late Archaic home groups of the lower Bosque had strong economic, and possibly linguistic and kinship, ties to central Texas groups.

There are other interesting things about some of the dart points, including a previously undefined type and uncharacteristically early ages associated with Ensor points, that may have broader implications for central Texas archeology. The Untyped Group 1 dart points, so prevalent at Higginbotham, are a previously undefined type. They may be associated with a regional late Middle to early Late Archaic tradition of long, thin, triangular-bladed darts with straight stems (e.g., Bulverde, Carrollton, Yarbrough, and Provisional Type 1), with the Waco Lake examples being a later, localized variant of these earlier, more widespread styles.

Ensor points from the Britton and McMillan sites, particularly those from Analysis Unit 2 at Britton and Analysis Unit 3 at McMillan, are associated with radiocarbon dates that are at least a few hundred years older than Elton Prewitt’s Twin Sisters phase (A.D. 200 to 550), of which Ensor is a diagnostic artifact. The unusually early dates associated with the Ensor points suggest that its initial appearance in the tool kits of ancient central Texans may have been in the Waco area.

These characteristics of the dart point assemblages from Waco Lake suggest that geographically restricted variants of point types, that is localized types, and temporal differences in the distributions of types may exist across the central Texas region. A greater scrutiny of dart point types, their variants, distributions, and temporal distributions across the region may lead to more meaningful discussions of social identity and social fields in the future, concepts that need greater attention in Texas archeology. In terms of Waco Lake, it is clear that during the Late Archaic there was a strong connection to central Texas proper, based on common dart point styles and other technologies and subsistence practices. The specifics of this connection, including the social dynamics underlying it, remain obscure, however.

If the early historic period mirrors the prehistoric, then the Late Archaic archeological pattern across the central Texas region is not the product of a single group or monolithic culture. Archeologist and ethnohistorian Mariah Wade identified 21 native groups who lived on the Edwards Plateau alone in the mid- to late 1600s. These groups composed an enormous socioeconomic network that was maintained through alliances, dual ethnicity, ladinos (individual translators, intermediaries, or facilitators between groups), and information sharing. Various groups formed coalitions and alliances based on common socioeconomic interests, the lifespans of which likely reflected the duration or resolution of those interests (e.g., resource inequities or threats from other groups). These alliances were often cultivated and sustained through the exchange of goods and information and initiated and facilitated by individuals of dual ethnicity or mutual kinship ties and ladinos.

Although Wade presents her analysis in the context of native groups’ relationships with Europeans in the early historic period, she clearly believes that these social mechanisms did not rise in response to the presence of Europeans. The complexity of these mechanisms indicates that they existed in prehistory as well. If such a network of common socioeconomic interests existed in prehistory—and there are no reasons to assume it did not—it would explain the regional patterns we see in the archeological record. It would explain how the Waco area was connected to the rest of the region even though multiple groups and ethnic and linguistic differences probably existed. The key to unraveling this is identifying local or geographically restricted variants of artifact types that signal social identity, not only for the Waco area but for the other regions it is connected to as well.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

If the early historic period mirrors the prehistoric, then the Late Archaic archeological pattern across the central Texas region is not the product of a single group or monolithic culture. Rather, the Waco Lake groups may have been part of an enormous socioeconomic network that was maintained through alliances, dual ethnicity, facilitators between groups, and information sharing.

In this exhibit we have focused on the resources used by the Bosque River people to meet the daily challenges of life during the Late Archaic period. Based on information recovered from the Britton, Higgonbotham, and McMillan sites during the Waco Lake project, several subsistence patterns are evident. |