Petrographic Analysis

Petrographic analysis is one of several methods used to help determine the source of raw materials used by prehistoric peoples, in this case, the clays used in their pottery. By comparing pottery sherds with samples of soils and/or raw clay from the site, analysts can determine whether the prehistoric pottery was made using local or non-local clay. Examining the physical structure of the clays and other materials that make up the paste used in constructing pottery provides insight into its composition and various constituents as well as clues to pottery-making technology. We also can use these results to determine if the same ceramic technology was being used at other sites, across different culture areas and through time.

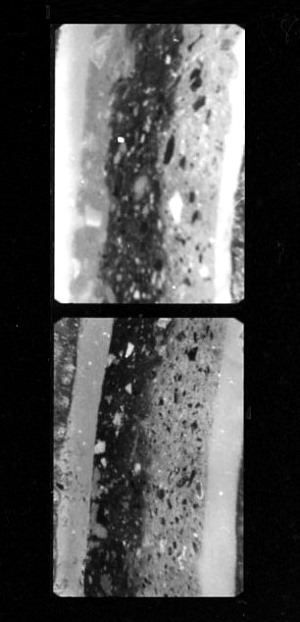

In order to do this, the prehistoric ceramic sherds first have to be sliced into minute thin sections and mounted on slides. Characteristics that scientists look for include identifiable particles of rock, rounded or angular grains, in the thin section. These might be bits of bone, quartz, feldspar, microfossils, chert fragments, etc. The presence and combination of the rock types provide information about the geologic source of the material and/or its components.

Twelve plainware pottery sherds and one local soil sample from the Varga site were selected for petrographic analysis. The pottery is from the Toyah interval of the Late Prehistoric period that ranges from 290 to 660 B.P. For comparative purposes five sherds from the historic San Juan Mission in San Antonio and three from the San Lorenzo Mission a few kilometers south of the Varga site also were sampled and examined.

Methods

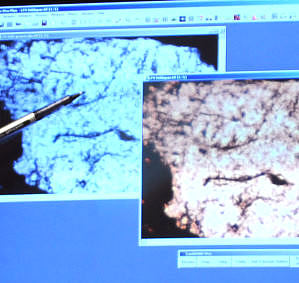

The principal method of study is viewing thin sections of potsherds under a high-powered microscope. This method provides fine-scale information on ceramic fabrics and the solid particles, termed inclusions, that are found in the ceramic fabrics of low-fired prehistoric wares. The many petrographic techniques for identifying bone, minerals, rock particles, and other bodies have been developed by the field of geology and its sub-branch of optical mineralogy.

The ceramic thin sections were stained for carbonates, and left without cover slips. Microscopic identifications and point counting were conducted on a stereographic Olympus microscope with rotating stage and polarizing light in the Microscopy Laboratory of the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, the University of Texas at Austin. Initially, the matrix colors of the sections were recorded under plain light, isotropy was determined, and the character of the matrix, voids, and inclusions was surveyed. Unidentified and unfamiliar bodies were sought for possible follow-on research and identification in published mineralogical literature. After this primary effort, the point-counting was conducted. The method involves a series of visual traverses of the thin section. Every body falling under the cross-hairs at regular intervals was counted and tabulated. Information included mineral or rock class and, for each class, size, shape, and incidental traits. Bodies large enough to cover the traverse interval were not counted twice. Bodies observed but not falling under the cross-hairs, thus not entering the point count, were recorded as trace. In this way all the observed contents of the sections could be reported. The point count halted at 200 counts. The voids and inclusions were classed for size by using the Wentworth size classification scale. The successful outcome of the point count permitted a quantified assessment of the attributes of the collection, a body of data comparable to other regional petrographic data, and manipulation by a variety of statistical measures.

Findings from Petrographic Analysis

The results of petrographic analysis of the Varga site sample identified a number of distinct paste groups. Analysis of a Varga site soil sample was valuable in distinguishing local from non-local paste groups and is a recommended strategy for future petrographic studies.

The Toyah component sherds at the Varga site are tempered with about 35 to 38 percent ground bone particles, with the exception of the one figurine-like object, which only has only about 10 percent ground bone. The 35 to 38 percent bone tempering is common to petrographic findings at other central Texas Toyah components such as the Rush site, Mustang Branch at Onion Creek, 41VV444, Buckhollow , and Currie at O. H. Ivie Reservoir. However, the average amount of bone, near 36 percent, for the Varga site Toyah sherds is some 12 percent higher than that detected at the Rush site, O. H. Ivie Reservoir sites, and the Onion Creek sites, where the average is about 24 percent, with a standard deviation of five percent.

The shared paste groups identified in the petrographic analysis for the Varga site Toyah sherds indicate similarity of technology. The current evidence supports a widely employed and basic Toyah technology that employed bone temper across most of central Texas. Variations in the amounts of bone temper and other additives reflect minor construction variability. Bone is definitely a characteristic of the Toyah ceramic assemblage, with variations in the amounts potentially reflecting behavioral variation between individual potters, vessel function, and/or clay conditions.

Variability lies largely with tempering agents and particles present in the ceramic clays. This variability comments more on function than style of pottery. Analysis of the Historic ceramics shows that Toyah bone-tempered ceramic technology persisted into the Historic Period with aboriginal populations who settled at Spanish missions. The aboriginal technology was gradually replaced by European technology and ceramics.

The identification of paste groups in the Varga sample collection was a useful way of ordering the data. Furthermore, the effort to identify paste groups shared with other sites and regions within the larger Toyah central Texas area was successful. The shared paste groups showed that locally produced ceramics were transported from site to site.

Various observations and interpretation of the petrographic analysis are summarized here. None of the Varga sherds exhibit a red slipped exterior surface as did several of the Buckhollow sherds. On the petrographic level, almost all the variability in ceramic pastes, temper, and clay residents revolve around gaining a successful ceramic vessel that survives its earthenware firing. In this, variability regards function, not style. On the technological level, variability refers to ceramic ingredients, modes of preparation, clay residents, and firing vagaries that can affect the outcome of the ceramics (interior carbon streaks, paste and bone colors, and other variables). It should be cautioned, however, that technological variability is only a partial list of total ceramic difference, and that typological variability is also crucial to understanding Toyah earthenwares and their changes.

From the petrographic analysis, the technology appears the same. Such traits as the angularity and sizes of tempering particles suggest consistent ways of preparing temper for addition to paste, hence the same recipe or step-by-step manufacturing sequence for the ceramics across regions and through time. A problematic issue is the observable variation in the amounts of tempering in the paste. Clearly, the differences in proportions of temper to clay made no difference to the success of firing the ceramics. The proportions of igneous, carbonate, and silicate tempers vary similarly in the pastes in which they are found. This shows the robustness of the earthenware technology, and that, within limits, temper proportions were in free variation and subject to individual potter choices.

Similarly, variability in the firing process itself appears to be consistent across the entire region and through time. Specifically, pastes and bone temper tends to have the same range of colors in their paste groups in all the sites examined. This suggests that the control of firing—temperatures achieved, atmospheres created and maintained, and other variables—was about the same in character and degree across the region and suffered the same vagaries.

Continuity can be seen between regions in the similarity of technology and shared paste groups, discussed in a following section. Shared paste groups show continuity through direct contact by a variety of mechanisms such as trade or movement in seasonal residential moves. Toyah ceramic technology indeed continued into the Protohistoric, where it was gradually replaced by Historic technologies.

Points of similarity between the Infierno phase defined in the Lower Pecos region during the Late Prehistoric and the Classic Toyah of central Texas during the same Late Prehistoric are: (1) earthenwares with oxidizing firings, (2) a commitment to bone tempering, and (3) use of local ceramic resources. On the third point, differences in the non-tempering inclusions demonstrate clear local acquisition of ceramic materials, and the analysis of the Varga site soil sample established one strong case study for the use of local clays. On the issue of local versus regional distinctions, this means that Toyah ceramics will most frequently have a strong local stamp, highly visible petrographically, especially the non-bone additives. The technological concepts of the ceramics, notably the ways additives are mixed into the ceramic, are shared region wide, from central Texas to the Lower Pecos, and thus are an overarching commonality. Strengthening this relationship is the detectable regional movement of a portion of the finished vessels. The scale and modes of this ceramic movement are just now being studied.

Comparisons between the prehistoric sites and the Historic Period missions show specific similarities and differences. The mission/prehistoric similarities are the above points. The difference is the adoption of new pastes and tempering sources, or an abatement of the common use of bone temper (although note that some prehistoric pastes also lack bone). In the Historic Period, we see the coexistence of several ceramic paste groups, followed by the gradual replacement of aboriginal technology.