Jornada Style Art

Looming down from the ceiling of a low shelter, this huge, goggle-eyed figure is awe-inspiring to viewers lying beneath. Spanning more than six feet, the black and white painting, thought by some to represent the Mesoamerican rain god, "Tlaloc," is filled with intricate designs formed by a seemingly continuous line. This quintessential Jornada Mogollon element may have derived from religious traditions in other areas. Photo by Rupestrian Cyberservices, courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. |

|

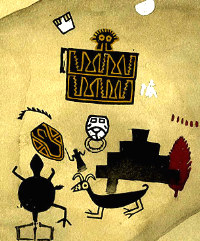

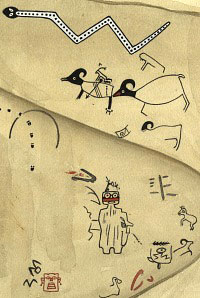

People of the Jornada Mogollon culture left a rich and distinctive legacy on the rocks during the roughly 1000 years that they periodically occupied Hueco Tanks. In contrast to the work of earlier Archaic people, the art of the Jornadans is characterized by a more sophisticated style encompassing a much broader repertoire of elements and motifs. Based on the large numbers of pictographs attributed to these people, it also appears that painting-as a ritual or artistic expression-played a large role in the lives of these foraging farmers. Among more sedentary people, the need for rain and favorable growing conditions for crops likely were critical concerns, expressed in rituals and conveyed through the painting of sacred symbols. Many of these symbols, thought to refer to water, lightning, clouds, and other natural elements, appear to hark back to more ancient times and far away places, where older cultures had similar concerns. At Hueco Tanks, these depictions, along with hundreds of masks, faces, dancing figures, animals, and other images, provide glimpses of the spiritual world of the Jornada Mogollon. Researchers have developed a number of theories as to what constitutes "Jornada style." The goggle-eyed figure found at Hueco Tanks and other sites is a key element of Jornada art, what anthropologist Helen Crotty deems the "quintessential Jornada image." Frequently referred to as "Tlaloc," in reference to a Mesoamerican rain deity, or "blanket kachina," in reference to figures prominent in later Puebloan cultures, the image incorporates a rectangular body filled with geometric stepped designs, a small head, and blank eyes. The Jornadans made use of step frets and stepped outlines in other depictions, including so-called "rain altars" or "cloud terraces." In Mesoamerican cultures, the stepped designs represented flowing water, energy, or lightning. Serpents, frequently portrayed in Jornada art, also are associated with water. Serpents wearing a horned or plumed cap appear in numerous rock art sites and have been likened to the Mesoamerican deity, Quetzalcoatl. Other elements in Jornada art also were inspired by the animal world. Horned sheep, antelope, and deer are typically painted with legs bent as if running. Birds vary from eagles with wings outstretched to long tailed songbirds. There are a variety of small reptiles such as turtles, snakes, and lizards. One feline animal, the subject of much conjecture by anthropologists, has been described as a collared jaguar, with obvious reference to Mesoamerican derivation. At Hueco Tanks, the Jornadans used a color palette of red, black, yellow, white, and a rare blue-green for their designs. Some were painted boldly across rock expanses, in some cases filling the surface. Others were painted in miniature, with remarkable attention to detail. Dots, lines, squares, and other patterns are used to fill and ornament numerous depictions. Locations for art appeared to have been chosen in some cases for the qualities of the rock "canvas" and in others for their obscurity. The Jornadans frequently filled small circular niches and weathered indentations in rock walls with paintings. In other cases, the artists created their work in "hidden" places-under boulders, in deep shelters, within narrow crevices, on ceilings, and on high walls of caverns. These obscure and difficult-to-reach locations speak to sacred rituals or perhaps "vision quests," involving individual journeys in search of identity. Some researchers have suggested that depictions of certain masks in some locales may signify clan affiliation or warrior societies. One of these sites, known as "Cave Kiva ," lies hidden high on a rocky hill and can be entered only by lying prone and pushing through a narrow slit under a massive boulder. On the other side is an expansive cavern with rock floor worn slick over the centuries by people sliding across the surface. Here the Jornadans painted a series of eight solid masks in bright red and yellow on the ceilings and walls. The crisp detail and precise placement of elements in the masks suggests they may have been stenciled rather than painted free-hand. Considering the Masks |

|

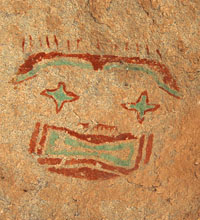

Examples of masks, or faces, at Hueco Tanks. Painted in shades of red, yellow, orange, and white, the masks incorporate a number of symbols, including lines extending from the eyes, an "x" or star, and in the third mask, a stepped "rain altar" on the right side. The latter was painted with more expressive features and with a definitive outline encircling the face. Photos by Rupestrian Cyberservices, courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. |

||

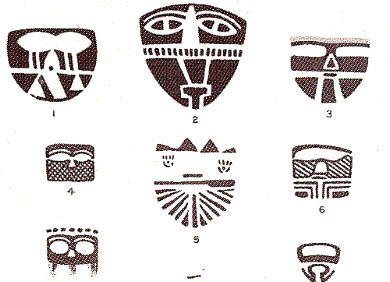

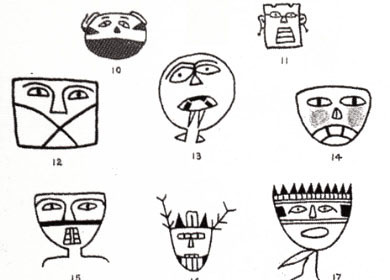

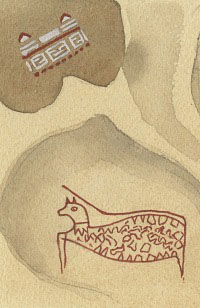

Masks at Hueco Tanks. Those in the plate at left have been classified as "solid" masks, which typically are more formal in design and precise in execution. The plate at right shows examples of "outline" masks in different shapes and with varied facial features: eyes with pupils, noses, and expressive mouths with teeth or tongues. Drawings by Dave Parker, courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife. Click camera icons to see more examples |

|

|

The masks in Cave Kiva represent only a small fraction of the known inventory painted at Hueco Tanks. More than 200 have been recorded at the site, constituting the largest assemblage in North America. Although masks and facial depictions appear at other sites, those at Hueco Tanks deserve special consideration, according to rock art specialist Polly Schaafsma, because of "their distinctiveness within the style and the degree of sophistication they exhibit." Artist Forrest Kirkland, one of the first researchers to comprehensively document Hueco Tanks rock art, classified the masks into two descriptive categories that are still used today: solid and outline. As with any classification scheme, there is considerable overlap between the two. Outline masks, also called linear masks, are face-like, often expressive, visages encircled by an outline. Typical features include almond-shaped eyes with pupils, an elongate or triangular nose, and mouths of various shapes. Black and white pigments were typically used for these depictions, and occasionally red. These masks closely resemble petroglyph, or carved, pecked, depictions at sites such as Three Rivers in New Mexico. Solid masks are more formal in appearance and generally lack a defining outline. Elements are commonly arranged in solid patterns, often in horizontal bands, with careful placement of negative spaces. Features typically include blank eyes in rectangular, almond, or circular "goggle" shapes; some have what may be beards and tongues. Painted chiefly in obscure locations at Hueco Tanks, solid masks may have had greater significance in ceremonies or rituals. Wearing of masks, headresses, and other adornment was—and still is —an important component of ritual life and ceremonies in many Native American communities. According to ethnographic and observer accounts, the ceremonialists and dancers would “become” the gods or deities symbolized by the masks. Anthropologists Kay Toness Sutherland and Polly Schaafsma have suggested that mask depictions at Hueco Tanks and other Jornada sites are evidence of a widespread ritual and religious system that strongly influenced the Anasazi and Pueblo kachina cults which appeared in the early to mid 14th century in New Mexico and greater Southwest. A number of the painted masks and depictions of masked dancers at Hueco Tanks appear similar to kachina masks. In "Spirits from the South," Sutherland points to kiva murals at the Anasazi Kuaua Pueblo, dating to roughly A.D. 1350, that include a number of elements similar to those of the Jornada Mogollon: the plumed or horned serpent, masked dancer, and a possible face with horned cap. Other researchers, including anthropologist Helen Crotty, acknowledge there are elements common in both art forms, but point out important differences in formal qualities of the two styles that indicate two separate artistic traditions. The mask depictions of both the Jornada people and the later Pueblo IV Anasazi people may represent cults involving masked dancing, but, she notes that the origins of these cults are probably rooted in an ancient and widespread belief system associated with the adoption of a desert land only marginally suited to it. "Clearly such a belief system would be too old and too widespread in the Southwest to be traced by the appearance of masks in Jornada style rock art at some time after 1050." Archeologist Darrell Creel, who has studied sites in the southwest and most extensively in the Mimbres cultural area of New Mexico, agrees that many of the symbols we see in both Jornada and Mimbres Mogollon art likely have underpinnings in a much more ancient time and are related to a larger Mesoamerican and southwestern transition—the beginnings of agriculture. Symbols for water and rain, such as rain altars, rain gods, and serpents, are common elements of societies in the western part of the continent, he notes. Although researchers now place the beginnings of agriculture in the New World at ca. 2000 B.C., there is no representational art known for that early time period. Archeologist Marc Thompson suggests that duality, or the uniting of features represented in twin or paired elements, may be further evidence of "participation in a widespread cosmovision," rather than long-distance diffusion. Aspects of dualism are represented in numerous depictions at Hueco Tanks and other Jornada Mogollon sites as well as at Casas Grandes, Mimbres, and Pueblo IV sites. Paired elements such as fish and "Venus" glyphs or stars are represented in several of the pictographs at Hueco Tanks, including a mask or face with paired four-pointed stars for eyes. Several masks are presented as pairs, including two with conical hats, and a pair of individuals wearing horned headdresses that appear facing each other in profile. Twins and pairs are common in classic Mimbres pottery. Artist Deborah Coolflowers is pursuing quite different leads in her study of Hueco Tanks art. She has attempted to correlate a pattern of elements and stylistic traits, or "signature characteristics," in several pictographs which she thinks may be the work of a "master artist." Among the characteristics she ennumerates are the use of red-orange pigment, depiction of earbobs on certain masks, as well as the use of dots, curvate designs, and interlocking crescents to fill in bodies of animals and what appears to be hair atop one of the facial depictions. Two pictographs bear a small symbol symbol resembling a short capital “T,” which she suggests may be the “signature” of the artist. The implications of this interpretation may prove interesting. A body of work attributed to a single artist speaks to someone having had the time and freedom to execute the works, someone perhaps connected to the small Hueco Tanks village site circa A.D. 1150. Just how much of the art can be attributed to the Hueco Tanks villagers is unknown, although radiocarbon dates on several goggle-eyed figures overlap the time of their occupation at the site. At the Three Rivers site in central New Mexico Jornadan peoples carved and pecked a number of images similar to those found at Hueco Tanks, including expressive faces, dancers, and characteristic geometric designs. The site appears to be associated with a small village (LA4921) dated to around A.D. 1100. Based on ongoing surveys, there appear to be many more pictographs at Hueco Tanks than is presently known. Computer enhancement of photographs also has detected previously unknown images, a selection of which are shown in the Hueco Tanks exhibit sections and in the section, Hidden Art. These include additional pictographs that eventually may aid in our understanding of Jornadan peoples. Many previously documented pictographs, however, have been obliterated because of weathering or human destruction. The Galleries of Forrest Kirkland watercolors included in this section allow viewers to explore copies of the pictographs as he saw them in the early 1930s, and see the remarkable imagery of the cultures living at Hueco Tanks.

|

|