Field Methods and Logistics

Vertical and horizontal controls were established to provide 3-dimensional recording. To serve as reference points, several metal pins were secured at convenient places along the back wall of the cave near the areas to be excavated. A vertical datum was established along the back wall and an arbitrary elevation of 100 meters was assigned to this mark. Elevations of all other vertical reference points were keyed to this vertical datum.

Horizontal control was maintained by working within conveniently sized and shaped excavation units which were established on a horizontal site plan. A grid system was not used so we could effectively align excavation units in respect to the undulating cave wall and patchy undisturbed deposits. Horizontal control did not suffer in the least and we gained the flexibility of placing units in promising areas in accordance to our research aims.

Most of the excavation work at Hinds Cave was carried out by using trowels and small whisk-broom brushes. Paint brushes, ear syringes, and other types of squeeze bulbs that would blow puffs of air were also used to excavate delicate deposits and sample fragile perishable items as needed.

To fulfill the goals of the botanical and coprolite studies, all excavated material from undisturbed deposits was screened through a dual screen apparatus. This apparatus was specifically designed for this project. It consisted of a conventional hardware-cloth screen with 1/4-inch mesh nested over a second screen with 1/16-inch mesh. The upper screen was used to sieve and sort the bulk or coarse material, pick out fire-cracked rocks, stone tools, perishable items, snail shells, and bone fragments. The coarse fraction, the fiber and bone residue that remained on the screen surface was then bagged. The fine screen below caught materials that were smaller than 1/4-inch square. This fine fraction was also bagged. In addition, for selected excavation units all of the dirt that passed through the 1/16-inch mesh screen was bagged and saved for later analysis. (A later study identified an additional 16 plant taxa from tiny seeds that went through the 1/16th mesh screen.)

While our sampling was the most thorough yet designed for a dry cave in the Lower Pecos, bags and bags of collected material began to accumulate. Each person was only able to carry out a maximum of about three to five matrix bags in a backpack on our decent at the end of the day, so far more bags accumulated than we were able to carry out. Either we had to devote a full day to nothing but carrying out bags, or figure out another way of getting the material back to camp.

The problem was solved, in part, by Vaughn Bryant and Ed Baxter. They designed a make-shift pulley device whereby pulleys were anchored on each side of Still Canyon. Plastic, nylon rope was used in the pulley system to transport a duffle bag used as a basket to carry matrix and artifact sacks across the canyon. We found that we could transport about 4 bags across the canyon per duffle bag. The canyon was over 300 feet across, so the looped rope had to be over 600 feet long. Despite the crudeness of the system, it worked. Two people were stationed on each side after lunch to start moving bags of material across. These four people worked four hours each day. By the end of each season we had successfully transported over 1600 bags of collected material without a single accident.

The pulley devise also was used to transport some of the equipment across the canyon as well. Once across, the bags then had to be carried from the canyon rim up the long slope to one of the trucks parked about ¼ mile from the canyon rim. From there, the hundreds of bags could be taken to our camp. On some days all of the bags had to be carried by hand from the rim to the camp. We devised a useful system for doing this by using army surplus stretchers, which we loaded with about a dozen bags and then two stretcher bearers would walk the samples back to camp. Every time a truck or van made the trip from our campsite back to the campus we always loaded it down with as many of the bags of material as we could. Otherwise, we would never have been able to transport all of those more than 1,600 bags of materials back to our lab on campus.

The campsite at the Hinds ranch was picturesque. The camp was on top of the plateau, breezy, with a view of at least 50 miles in most directions. Even the Burro Mountains in Coahuila, Mexico were clearly visible from our vantage point. At night there were no city lights in sight so we could get a clear view of the major star constellations and the Milky Way. To get to our camp near the old Hinds ranch house, however, it took three hours from Del Rio driving through three different ranches and nine wire gaps (fence "gates"), many of which were locked so we had to stop to unlock and relock each one.

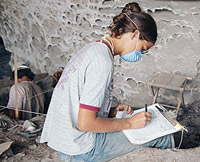

The field camp comprised a “tent city” of a dozen or more brightly colored units, which were set up in proximity a cattle tank and well. The well served as a water supply and the water tap was outfitted with an invigorating and refreshing cold shower—the water came from 600 feet down. Excavating a dry rock shelter is comparable to working in a coal mine; the dust penetrated even the most tightly woven garment. This is why each day each person working at the site was given an ample supply of paper, disposal surgical masks. That was the only way to keep “most” but not all of the dust out of our lungs. At the end of each day the exposed portions of our bodies were blackened with cave dust. The only non-blackened areas were small circles around our noses where the surgical masks had been used. Supplying the camp with food was also challenging, and involved sending a van on a 12 hour round trip to Del Rio about once every three days.

The hike to Hinds Cave from the camp was not a breeze either; it was over two kilometers down the slope toward the Pecos, then down into Still Canyon, and up a nearly vertical 65-foot climb to the cave. The climb up was steep and required the use of a rope and both hands. In a few places we even built short ladders in especially steep areas. The decent and climb out was not easy either, especially since everyone had the added weight of at least three bags of materials collected from the screens. The descent also required the use of both hands. That meant everything initially brought into the cave either had to be hoisted up with a rope or carried in backpacks. Each person was required to carry at least one full gallon of water to the site each day. Because of the heat it was easy to become dehydrated and the closest fresh water was the well near our campsite. We had to carry our lunch in each day, except for jars of peanut butter and jelly, which we left in the cave. One sandwich of lunch meat and vegetables and one of peanut butter and jelly plus fruit was the lunch cuisine for both field seasons. The physical effort of the logistics was the most physically challenging archeological project that either of us (Shafer and Bryant) had been on, but it also was one of the most worthwhile.