Baffin Bay

This narrow bay 70 miles south of Corpus Christi forms the boundary between the arid lower Texas coast and the better-watered central Texas coast. Its distinctive three-fingered shape reflects the bay’s formation during the Pleistocene as the upper part of a small river valley that drained into the Gulf of Mexico over 30 miles to the east of the modern shoreline. During the mid Holocene the valley flooded as sea level rose and an ancestral Baffin Bay formed in which oysters and other shellfish thrived. But by about 3,000 years ago the extensive barrier island known today as Padre Island had formed cutting off Baffin Bay’s direct access to the Gulf. The bay filled with sediment and its shallow waters became hypersaline and less productive for many species (except certain fin fish) than any of Texas’ other bays, a condition which helps explain its prehistoric record.

Although the archeology of the Baffin Bay area remains poorly known, intriguing reports from geologists, marine biologists, and artifact collectors have piqued the attention of researchers for over 60 years. In the late 1940s geologist Armstrong Price reported the finding of a Mesoamerican-style figurine and a stone gorget with an eroded human burial near the mouth of Baffin Bay. In the 1950s marine biologists observed oyster shell middens at several sites along the shores of Baffin Bay and reasoned that these must represent use of the area during a wetter period before the modern, hypersaline bay formed.

In 1967 Thomas R. Hester carried out reconnaissance in Kleberg and Kennedy Counties at the western end of Baffin Bay around Cayo del Grullo and Laguna Salada, and inland to the west. He revisited some of the Baffin Bay localities previously reported and recorded several dozen additional sites, noting that most were badly eroded and had similar kinds of debris. Most sites were characterized as having many baked clay lumps (substitute cooking stones?) and considerable quantities of land snails and, near the bay, marine shell. Stone artifacts were relatively uncommon, but included a modest number of Archaic dart points (most would probably be considered Late Archaic types today), and quite a few arrow points. Most projectile points were of triangular styles characteristic of south Texas and the adjacent coast. Hester also documented extensive evidence of the use of human bones to make hollow tubes, rasps, and beads, all of which appeared to have been deposited as grave goods.

Before discussing the archeological record of Baffin Bay any further, its geological and ecological characteristics need explication.

Baffin Bay Setting and Ecology

Baffin Bay is fed by small intermittent streams that collectively drain a small area of the South Texas Plains typified by high temperatures and low rainfall. With limited freshwater inflow, evaporation far exceeds precipitation, resulting in a hypersaline estuary. During prolonged droughts the salinity level can spike to over 100 parts per thousand (average seawater level is 35). More than any other bay in Texas, Baffin Bay lives in a fragile balance facing high salinity cycles when inflow ceases and summer and winter temperatures become extreme. Species sensitive to environmental changes compete against nature more than with each other. Although faunal and floral inventories by biologists show that today’s Baffin Bay has a limited range of species and totally lacks the shellfish humans exploited for food (e.g., oyster, rangia, quahog, etc.), it is renown for its large spotted seatrout and black drum.

Baffin Bay lies at the northern edge of a distinct geological formation called the South Texas Eolian Sand Sheet. Although there are intact dune fields within, most of the area is a sand prairie that formed over tens of thousands of years as windblown sand derived from ancient shorelines that once existed across the continental shelf. The Sand Sheet extends southward about 60 miles from the south side of Baffin Bay to the Rio Grand Delta and about 75 miles inland. Today the area supports an oak savanna.

Much of Baffin Bay, especially its north side, is ringed by clay-dune bluffs behind which are flat upland clay prairies. The distinctive clay dunes formed during the Holocene from sediment from dried up playas (shallow lakes that existed during the cooler wetter times of the Pleistocene). Clay dune formation requires a combination of factors: shallow marginal mud flats, strong and unidirectional winds, and hot, dry conditions. The dunes formed by windblown clay pellets generally have a low-angle slope and stabilize rapidly creating transverse ridges that follow salt-flat margins. Over time, the clay dunes become compacted and flattened and support an impoverished plant community.

Human History

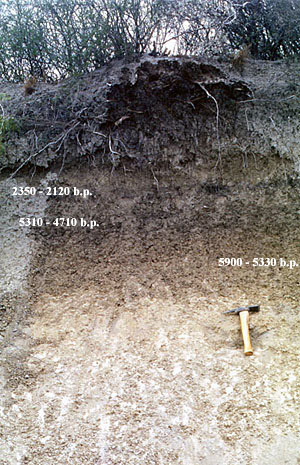

Although a few scattered Late Paleoindian points have been found in the area, these represent use of the valley in which the bay later formed. The earliest documented human occupation of Baffin Bay comes from several sites overlooking Cayo del Grullo. The Laureles site (41KL71) has seen the most archaeological investigations, and was originally noticed eroding out of a bluff. As reported by Herman Smith in his 1986 dissertation from Southern Methodist University, it is a multi-component site with three occupations layered in fifteen distinct strata.

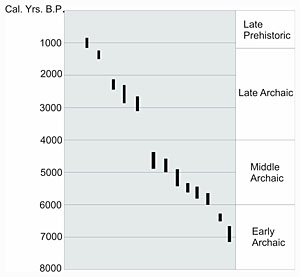

In the 1990s Robert Ricklis revisted the Laureles site and several others along the north shore of Cayo del Grullo and the north shore of Baffin Bay proper. He recorded and sampled clay dune stratigraphic profiles as part of a larger research project studying sea level change. He obtained over a dozen new radiocarbon dates on distinct occupational layers, noting whether or not these were associated with shellfish collecting. All those evidencing oyster harvesting dated before 2,000 B.C.

The earliest occupation at the Laureles site was buried about 2.5 meters below the modern bluff surface and yielded a radiocarbon date of about 3300-3900 B.C. for what Smith characterized as an “Early Archaic” occupation. (The date falls within what is considered the Middle Archaic period today). Five hearths were documented along with several clusters of shellfish, lumps of fired clay, and a single biface. The most prevalent marine shell was the Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea verginica), but hearths also had lightening whelk, tulip conch, and bay scallop. These shellfish species require considerably lower salinity levels that can be found in Baffin Bay today and, in the case of at least the lightening whelk, far deeper water. The deep oyster-harvesting occupation was capped by clay dune formation, showing that it was followed by a period of aridity.

As reconstructed by Ricklis (see Changing Sea Level), the modern bay systems and barrier islands of the Texas coast had formed shortly after sea level stabilized at its present position around 1000 B.C. Baffin Bay had probably become hypersaline by this time, however during the remaining 2500 years of prehistory the bay system saw its most intense use and subsistence patterns expanded to include fishing, foraging, and hunting seasonal waterfowl and game. Small cemeteries were established around the bay in which some rather unusual ritual items were left as grave goods. Virtually all known aboriginal sites in the Baffin Bay area seem to have components dating to the final two millennia of prehistory especially during the Late Prehistoric period after about A.D. 1200.

Smith investigated three sites with Late Archaic components, two on Cayo del Grullo (the Laureles site and 41KL37) and one on the northwest shore of Alazan Bay (41KL74). These yielded several radiocarbon dates 2,000-2,200 years ago. Late Archaic deposits had few or no shellfish, but had numerous otoliths from unusually large black drum. Smith argued that these represented winter fishing camps. This seems to fit the biological model that vertebrate species (fish) tend to be larger in hypersaline environments, while and invertebrates (such as shellfish) tend to be smaller.

The Late Prehistoric period after A.D. 1200 represents the apogee of aboriginal occupation around Baffin Bay. Cameron, Fresno, and Starr triangular arrow points, Perdiz points, and Rockport pottery are the most common diagnostics, but earlier expanding stem Scallorn arrow points also occur. Continuing a pattern seen at Late Archaic sites, the sunray venus clam from shallow Gulf waters was a preferred material for shell scrapers.

The Late Prehistoric site that has seen the most concerted investigation is the Loyola Beach site (41KL13), which was originally recorded in 1941 by G. E. Arnold during site reconnaissance of the area on a WPA project through UT-Austin. In 1967 Hester revisited the site and arranged for several artifact collections to be donated to TARL. His 1971 report on the site documented several hundred pottery sherds along with a variety of stone and shell artifacts, deer bones and other faunal remains, baked clay lumps, black drum bones, and dense quantities of land snails. The finding of Perdiz points, small end scrapers, small flake drills, and small prismatic blades coupled with the Rockport pottery clearly points to a Rockport phase occupation.

In the early 1980s Smith returned once again to Loyola Beach and carried out excavations. He felt the site reflects a permanent or regularly used space with distinct activity areas. Over 2,000 fish otoliths were analyzed. The overwhelming majority were from black drum, harvested in the late fall or early winter. Smith argued that the site served as a base camp or a processing station for extracting fish oil stored (and presumably transported elsewhere) in asphaltum-coated Rockport pots.

Not far from Loyola Beach site is “Indian Hill” or the Dietz site (41KL14), a cemetery site at which several dozen graves were dug up by amateurs in the 1930s. In a short and sketchy 1937 article, Clyde Reed reported the finding of two cloud-blower type stone pipes from one grave. One pipe had a bone mouth piece that was later identified as a section of a human ulna. A collection of 17 large “bone beads” from that site were found to consist mainly or wholly of sections of human long bones that had been fashioned by the groove and snap technique. Hester reported these in a 1969 American Antiquity article along with 22 more carefully studied human bone artifacts from Pescador site (41LK39), directly across Cayo del Grullo from the Loyola Beach and Dietz sites.

The bone artifacts from the Pescador site were made from human long bones including femur, tibia, fibula, and radius as well rib bones. They were fashioned by the groove and snap technique after which the snapped edges were smoothed. One is decorated with a zig-zag pattern of incised lines highlighted by red ochre; on the opposite side are closely spaced parallel incised lines like those found on musical rasps. Several appear to be polished, perhaps by extensive handling. Scattered and unaltered human bones were found in the same area strongly suggests the human bone artifacts were grave goods.

This unusual practice is not unique to Baffin Bay, although the area has yielded the bulk of the known specimens. A single example of a human bone tube made from a tibia section that has adhering red and black pigment was found at the Cayo del Oso cemetery on the south side of Nueces Bay. Human bone tubes are also known from several sites in Cameron and Hidalgo counties in the Rio Grande delta as well as sites in northeastern Tamaulipas, Mexico. This suggests that the origins of this pattern lie to the south of Baffin Bay.

Contributed by Suzanne Smith and TBH editor Steve Black.

Sources

Hester, Thomas R.

1969a Archeological Investigations in Kleberg and Kenedy Counties, Texas in August, 1967. State Building Commission, Archeological Program Report 15.

1969b Human Bone Artifacts from Southern Texas. American Antiquity 34(3): 326-328.

1980 Changing Salinity in Baffin Bay, Texas, and its Possible Effects on Prehistoric Occupation. In Papers on the Archaeology of the Texas Coast, edited by Lynn Highley and Thomas R. Hester, p. 105-108. Center for Archaeological Research, University of Texas at San Antonio, Special Report 11.

Highley, C. Lynn

1980 Archaeological Materials from the Alazon Bay Area, Kleberg County. In Papers on the Archaeology of the Texas Coast, edited by Lynn Highley and Thomas R. Hester, p. 61-78. Center for Archaeological Research, University of Texas at San Antonio, Special Report 11.

Ricklis, Robert A

2004 Prehistoric Occupation of the Central and Lower Texas Coast. In The Prehistory of Texas, edited by Timothy Perttula, p155-180. Texas A & M University Press, College Station.

1999 Atmospheric Calibration of Radiocarbon Ages on Shallow-Water Estuarine Shells from Texas Coast Sites and the Problem of Questionable Shell-Charcoal Dating. Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society 70:479-488.

Ricklis, Robert A. and Bruce M. Albert

1998 Response of Fluvial and Barrier Island Sustems to Climate and Sea Level Change: the Geoarchaeological and Palynological Evidence. Final Project Report submitted to the National Science Foundation, Geography and Regional Sciences Program. On file, TARL.

Smith, Herman

1986 Prehistoric Settlement and Subsistence Patterns of the Baffin Bay Area of the Lower Texas Coast. Unpublished dissertation. Southern Methodists University, Dallas.

Tunnell, John Wesley, Frank W. Judd, Richard C. Bartlett

2002 The Laguna Madre of Texas and Tamaulipas. Texas A& M University Press, College Station

Greenstone figurine reportedly found by a man working for geologist Armstrong Price in 1947 near the mouth of Baffin Bay along with a polished stone gorget similar to those found in Adena sites. Alex Krieger asked leading Mesoamerican scholars of the day including Matthew W. Stirling of the Smithsonian Institution to examine the figurine. They noted that it was quite similar to those found at La Venta and other Olmec sites and was most likely made in Guerrero, the source of the serpentine the figurine is made of.

|

The South Texas Sand Sheet reflects tens of thousands of years of sand accumulation blown in from former shorelines that once existed across the continental shelf. Today the area supports an oak savanna and has no surface water. Adapted from Ecoregions of Texas map, Environmental Protection Agency.

|

|

Radiocarbon dates from the northern shore of Baffin Bay and its extension Cayo del Grullo obtained by Robert Ricklis. The dates from Early and Middle Archaic deposits are associated with oyster-bearing components, while the dated Late Archaic and Late Prehistoric deposits contexts lack evidence of oyster harvesting. Graphic by Robert Ricklis.

|