About Darts, Atlatls, and Other Weaponry Systems |

Atlatl hunting system and elements. At left, a hunter hurls a dart from atlatl (drawing by Ken Brown, TARL); center, atlatl handle fragment (Peabody Museum, Harvard University); right, pointed foreshafts from Ceremonial Cave (TARL Collections); bottom, atlatl replica (Peabody Museum, Harvard University). |

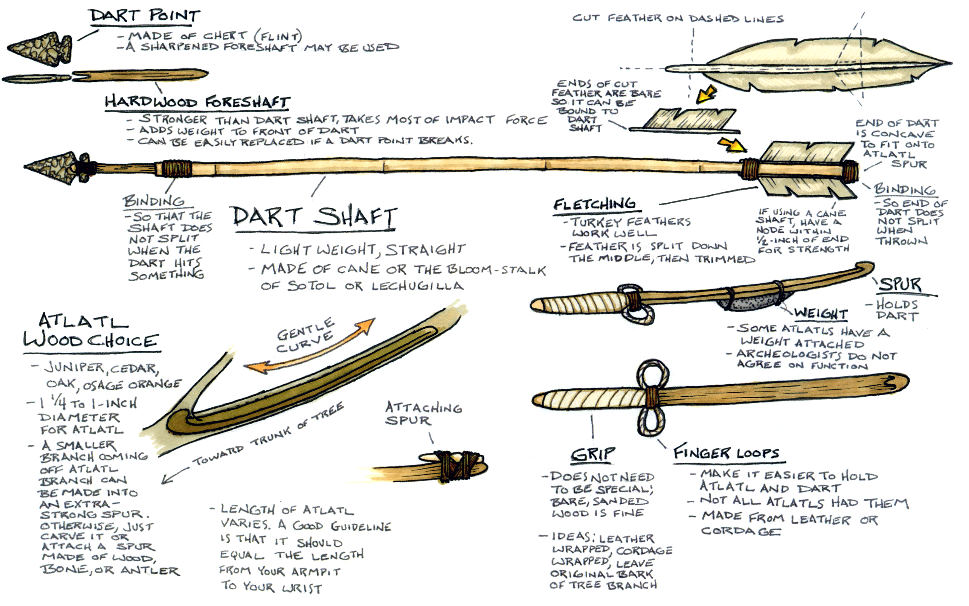

Materials for constructing an atlatl and dart. Enlarge to see full graphic. Drawing by Jack Johnson |

Weapons for Small GameThe atlatl and dart weapon system was more suitable (or needed) for hunting large game animals such as deer, bighorn sheep, and bison. For smaller animals, hunters used snares, traps, or less complex weapons, including sharpened wooden darts, which could be thrown or jabbed as spears. Curved wooden throwing sticks, or “rabbit sticks,” also could be hurled at small game. In concept, they are not unlike the Australian boomerang, although rabbit sticks do not return to the sender. Also, known as fending sticks, the curved sticks may been used as weapons, for warding off blows in battle. The specimens shown at right could have been used for these and other purposes. The stick shown on left has been made into a wrench used for straightening spear or dart shafts. The two specimens at far rightare unusually large for rabbit sticks. Hunters also employed wooden bunts, rather than sharp dart points, to dispatch some types of prey. Hafted to the end of a weapon, a wooden bunt effectively stunned the animal without damaging the animal’s valuable fur or feathers. It could then be dispatched with a subsequent blow from a rabbit stick or other weapon, or by strangulation. The shift from the atlatl and dart to the bow and arrow ca. between A.D 500-1000 was a change in weapons technology that occurred across all of North America. The greater efficiency, range, and mobility provided by bow and arrow technology no doubt made it a preferred weaponry system. With the well-preserved perishable specimens from Ceremonial Cave and other sites in similar arid settings, researchers are able to form a more complete picture of the weapons and hunting technologies used by prehistoric peoples, including how the various devices were made and how they were employed. Some were elegant in their simplicity, others involved a more intricate system of multiple parts. With studies underway on addtional specimens, a great deal more can be learned about the ingenuity and culture of the Ceremonial Cave craftsmen. |

|